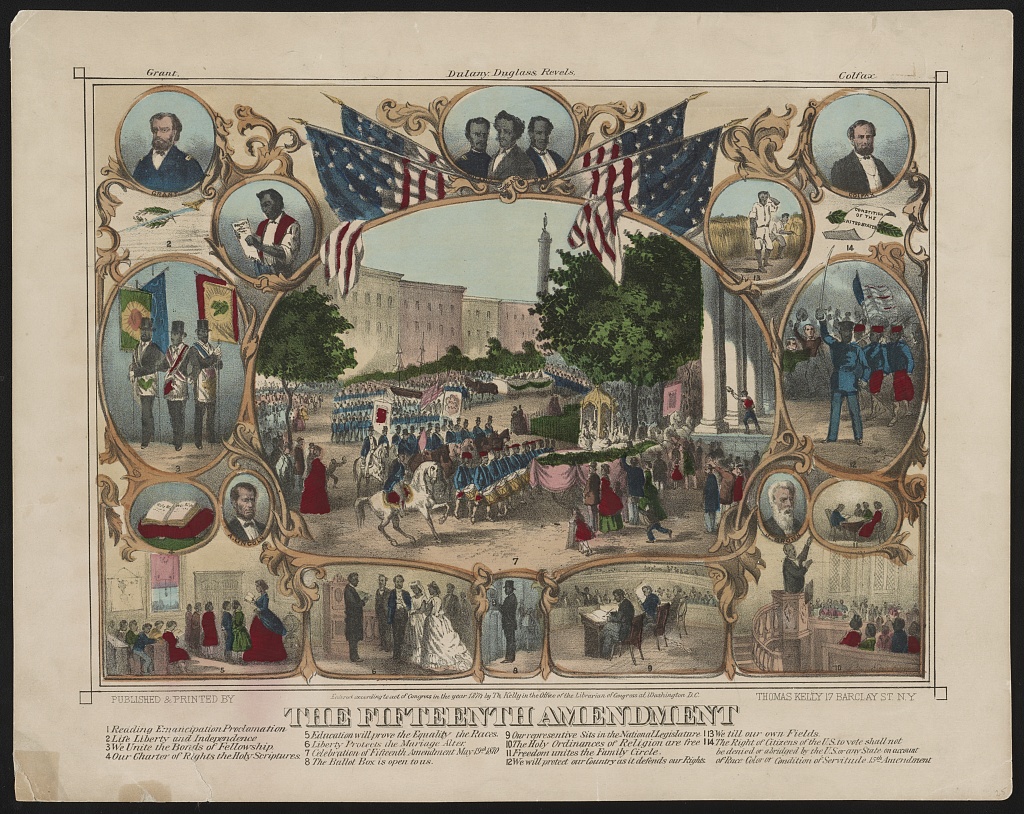

Universal suffrage proposals first emerged during the Reconstruction era (1865-1877). Suffragists later modeled their proposal after the 15th Amendment (1870) and settled on language to end sex discrimination in voting. First proposed in 1878, the “Susan B. Anthony Amendment” was introduced in each Congress—unchanged—for the next four decades. Congress finally approved it on June 4, 1919. The 19th Amendment was ratified on August 18, 1920.

Special thanks to Reva Siegel of Yale Law School for sharing her advice and research in “She the People: The Nineteenth Amendment, Sex Equality, Federalism, and the Family” and to Laura Free from Hobart and William Smith Colleges for reviewing this content.

Turn device horizontally for easier scrolling.

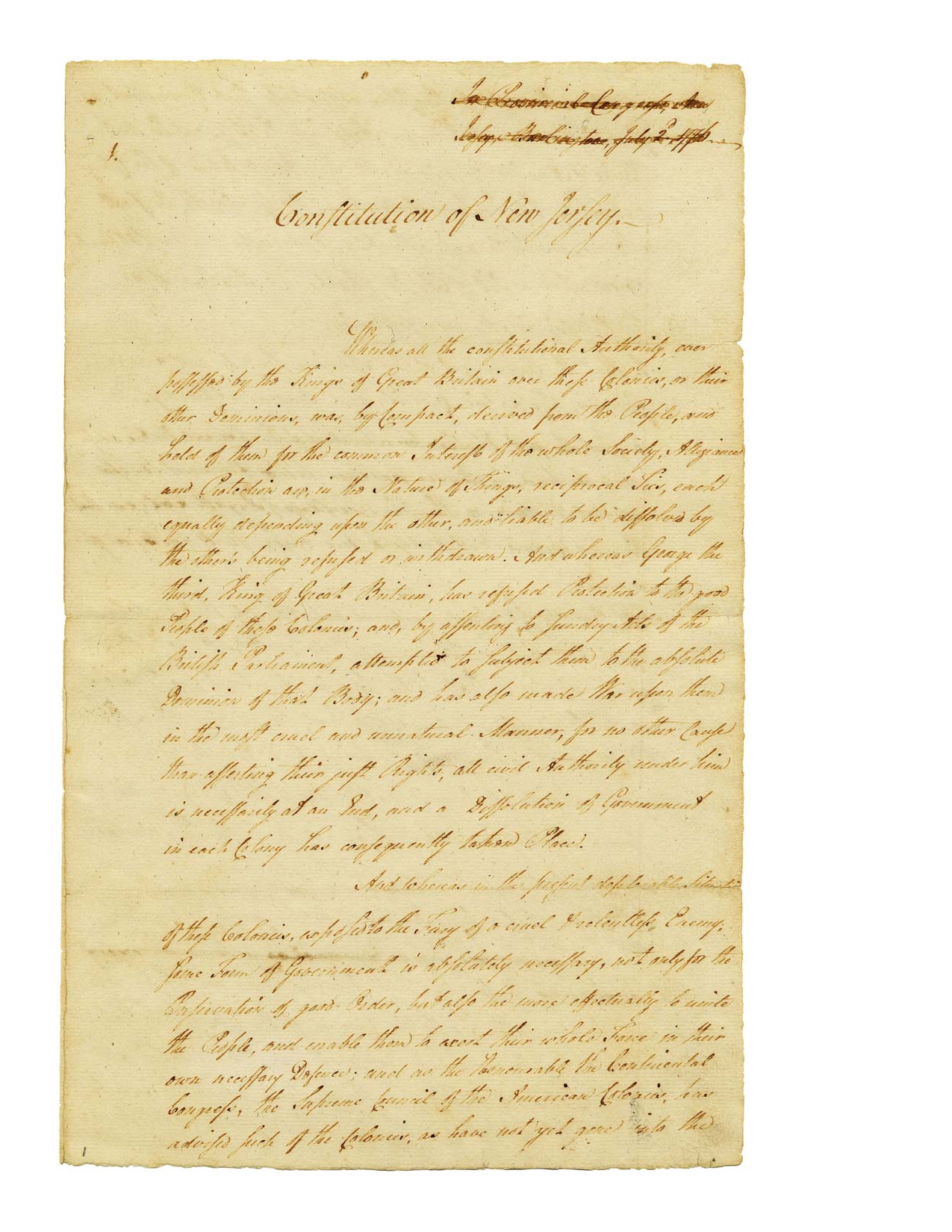

Event — July 2, 1776

Event — June 12, 1840

Event — April 7, 1848

Event — July 19, 1848

Event — April 12, 1861

Event — April 9, 1865

Event — December 6, 1865

Event — May 10, 1866

Event — July 9, 1868

Draft — December 7, 1868

Draft — December 8, 1868

Draft — January 29, 1869

Draft — March 15, 1869

Event — May 15, 1869

Event — December 10, 1869

Event — February 3, 1870

Event — November 5, 1872

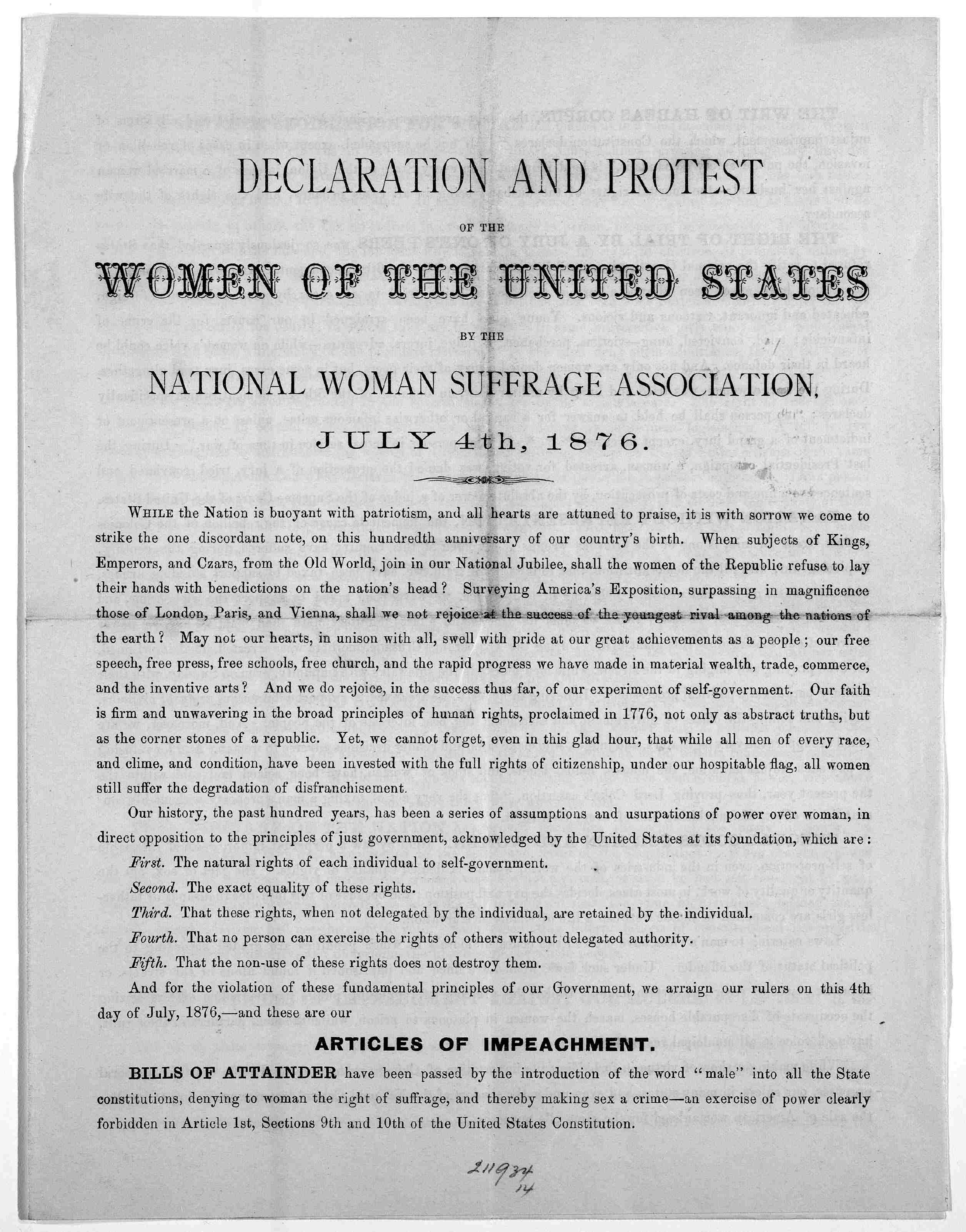

Event — July 4, 1876

Draft — January 10, 1878

Draft — July 10, 1882

Draft — March 28, 1884

Event — February 18, 1890

Event — January 1, 1911

Event — March 3, 1913

Draft — March 19, 1914

Draft — March 19, 1914

Draft — March 20, 1914

Event — January 10, 1917

Event — April 6, 1917

Event — November 6, 1917

Event — January 10, 1918

Event — June 4, 1919

Draft — June 4, 1919

Event — August 18, 1920

In 1776, New Jersey didn’t restrict voting to men in its state constitution. Women who met certain qualifications voted until 1807, when the state passed a law restricting voting to “free, white, male citizen[s].” Most other states limited voting rights to white male property-holders. Under this system, few people could vote.

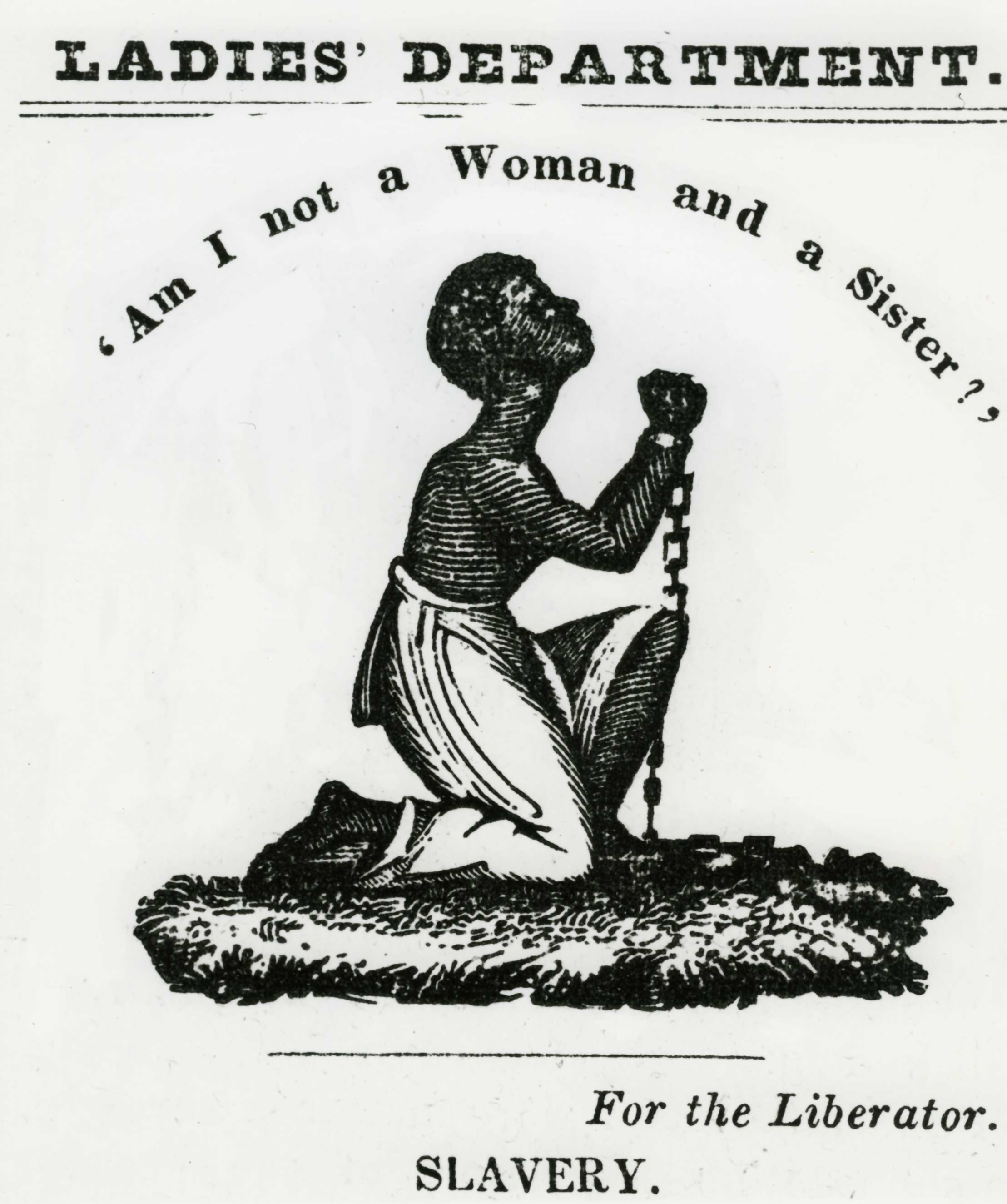

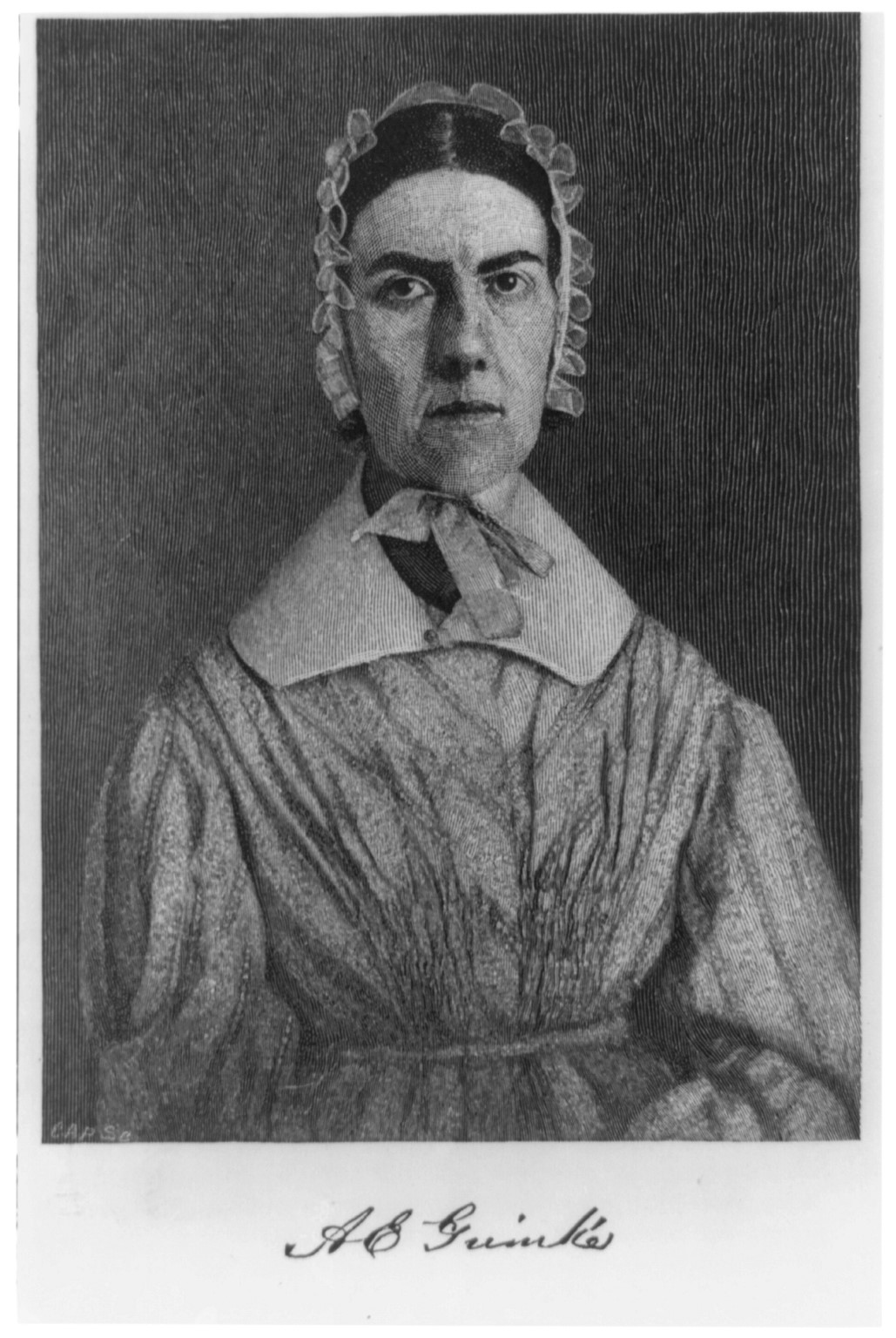

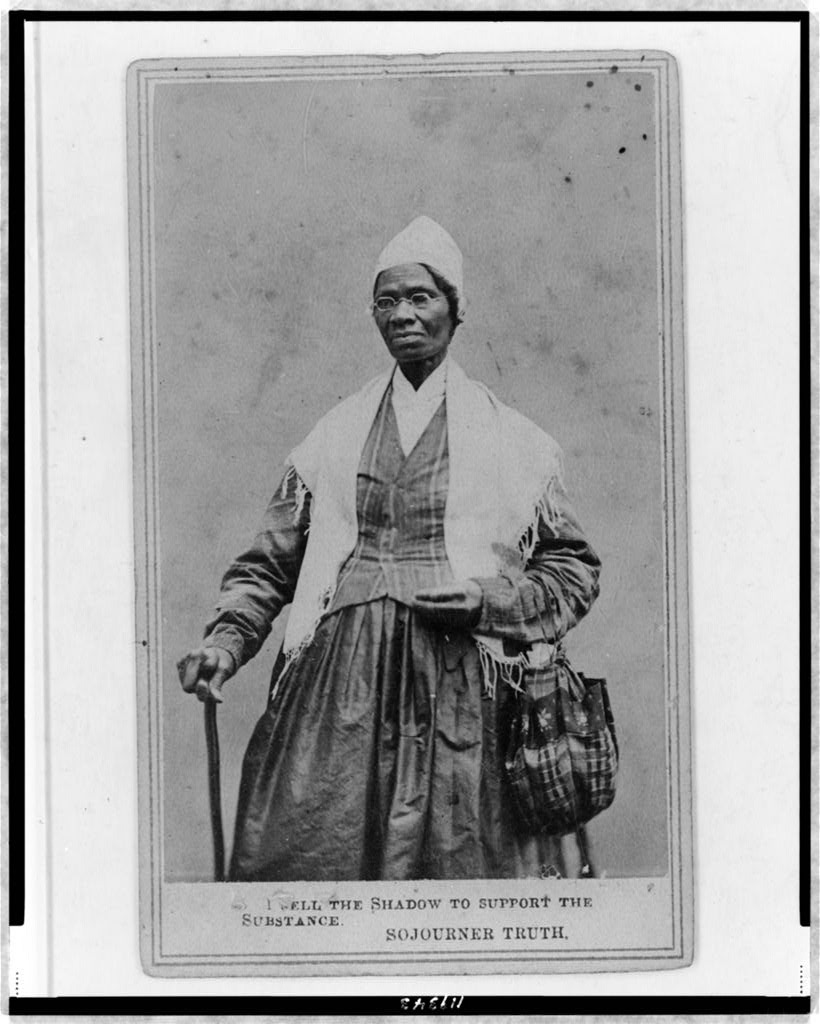

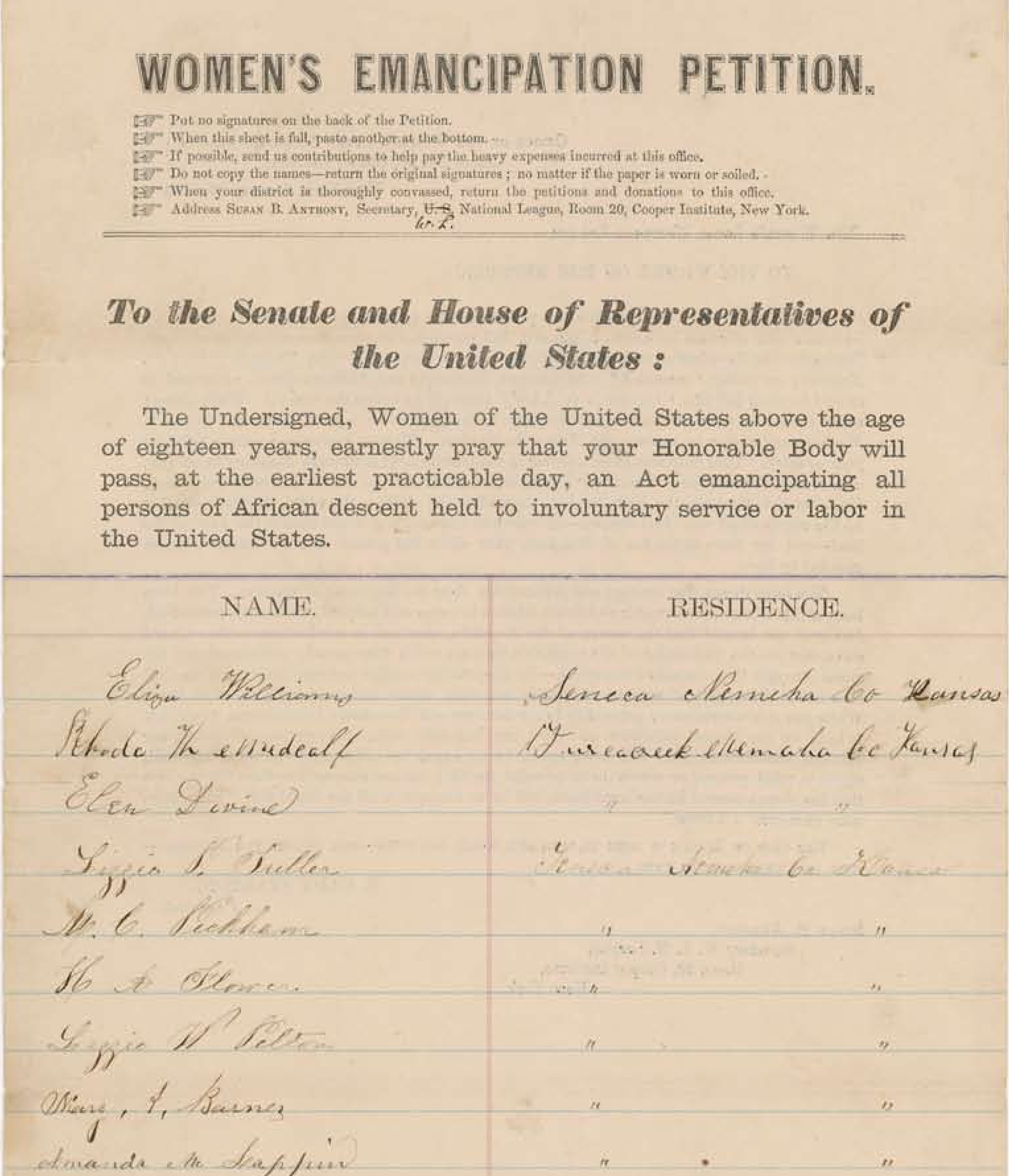

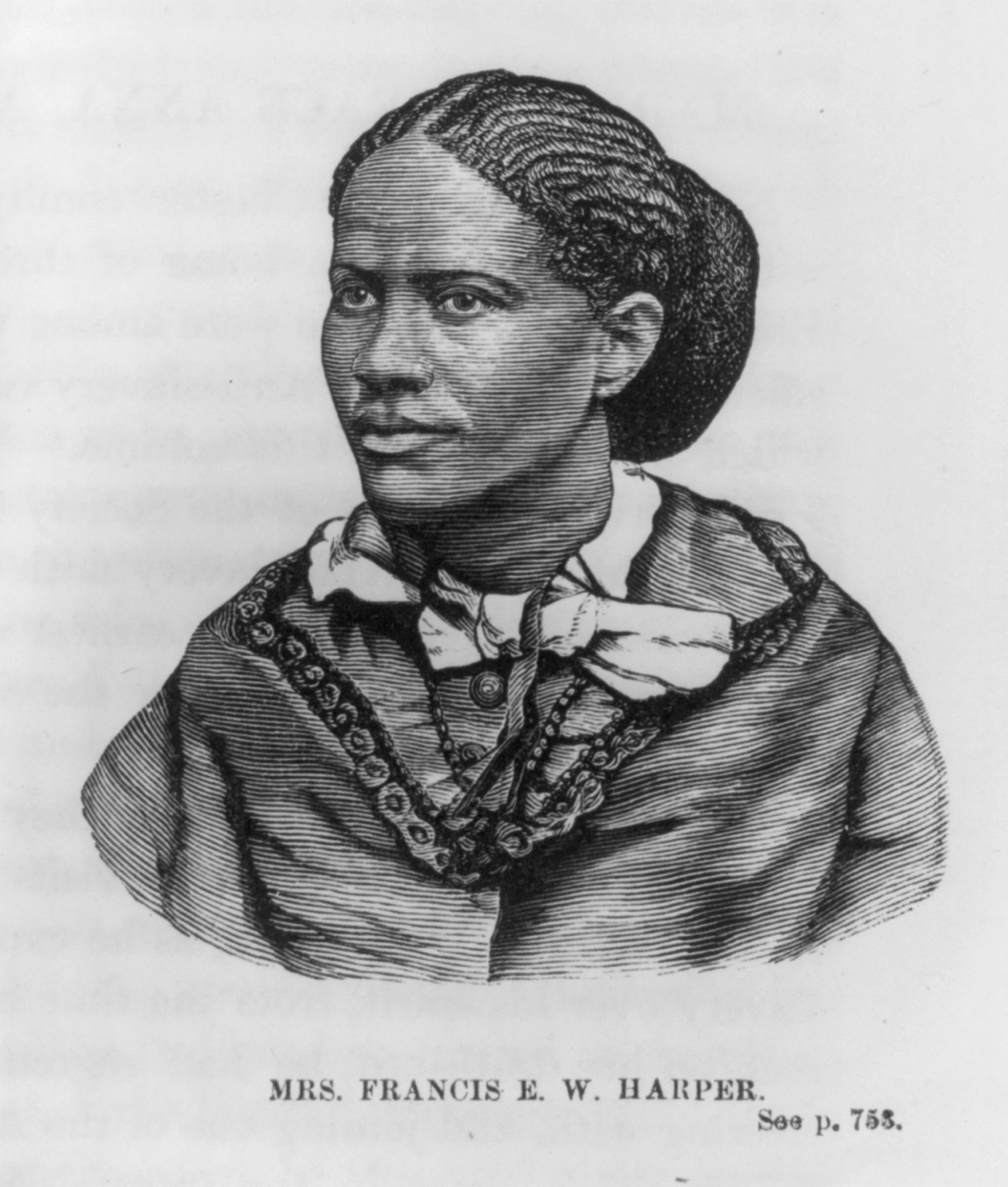

Many women participated in the anti-slavery movement. They petitioned Congress and fought for the right to speak in public. Later, they adopted the constitutional arguments at the core of the anti-slavery cause. When the World Anti-Slavery Convention met in London, women were forced to sit in the gallery. William Lloyd Garrison and others joined them, refusing to take their seats in solidarity.

Under the legal doctrine known as “coverture,” married women couldn’t sue or be sued, enter into contracts, or hold property of their own. The early women’s rights movement challenged this system and secured key victories even before the Seneca Falls Convention—most notably, when married New York women gained the right to hold property.

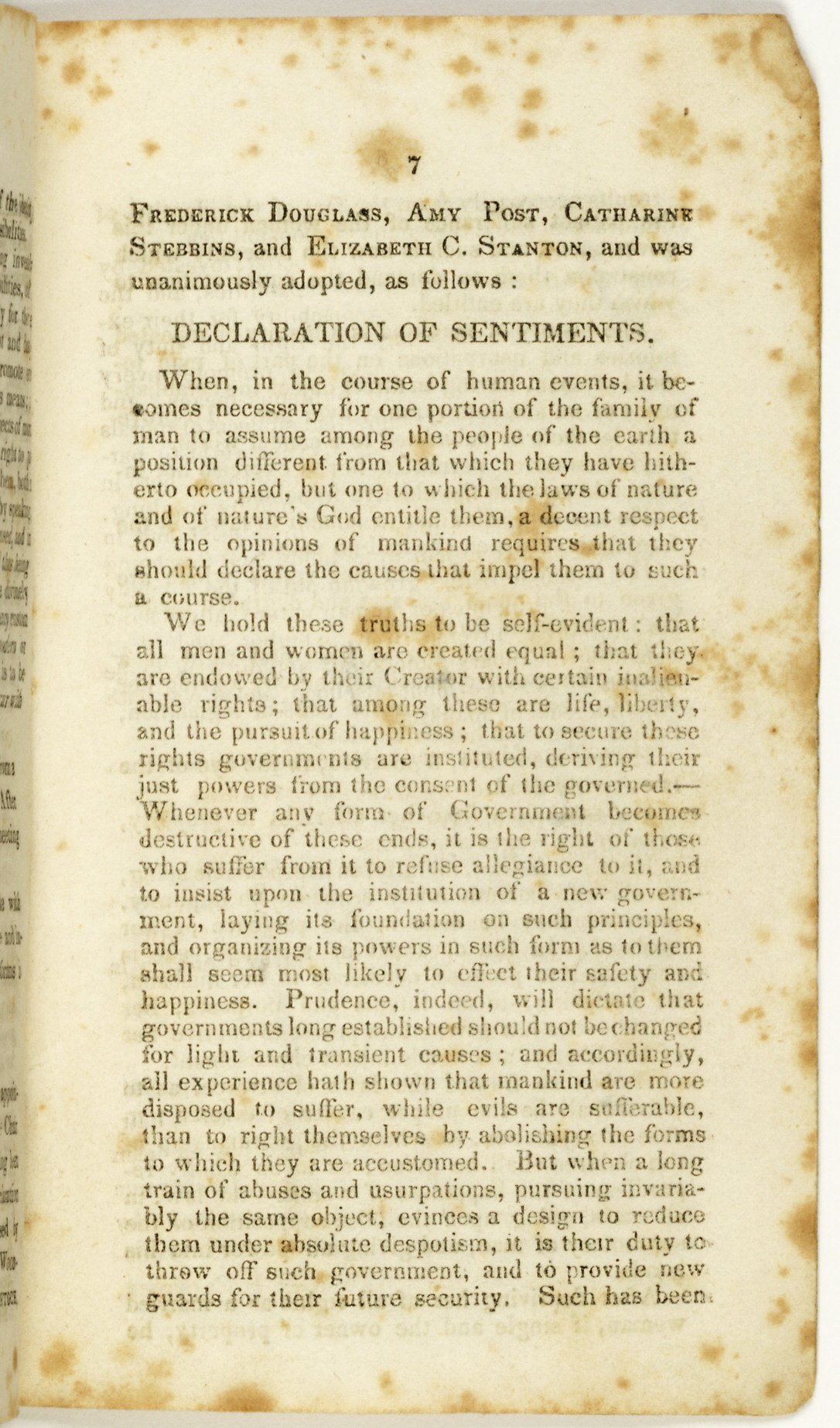

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women’s rights convention in American history. It attracted nearly 300 people and produced the famous Declaration of Sentiments, which included a resolution for voting rights. Although the gathering endorsed women’s suffrage, the burning issues of the day centered on married women—and their right to contract, own property, and sue or be sued.

As war broke out at Fort Sumter, women’s rights advocates paused their work to focus on the war effort and slavery’s abolition. Women organized societies to encourage soldier enlistment, sew military flags, prepare soldiers’ supplies, raise money for the troops, and petition against slavery. Women also worked in the medical profession and replaced men in factories, stores, and the patent office.

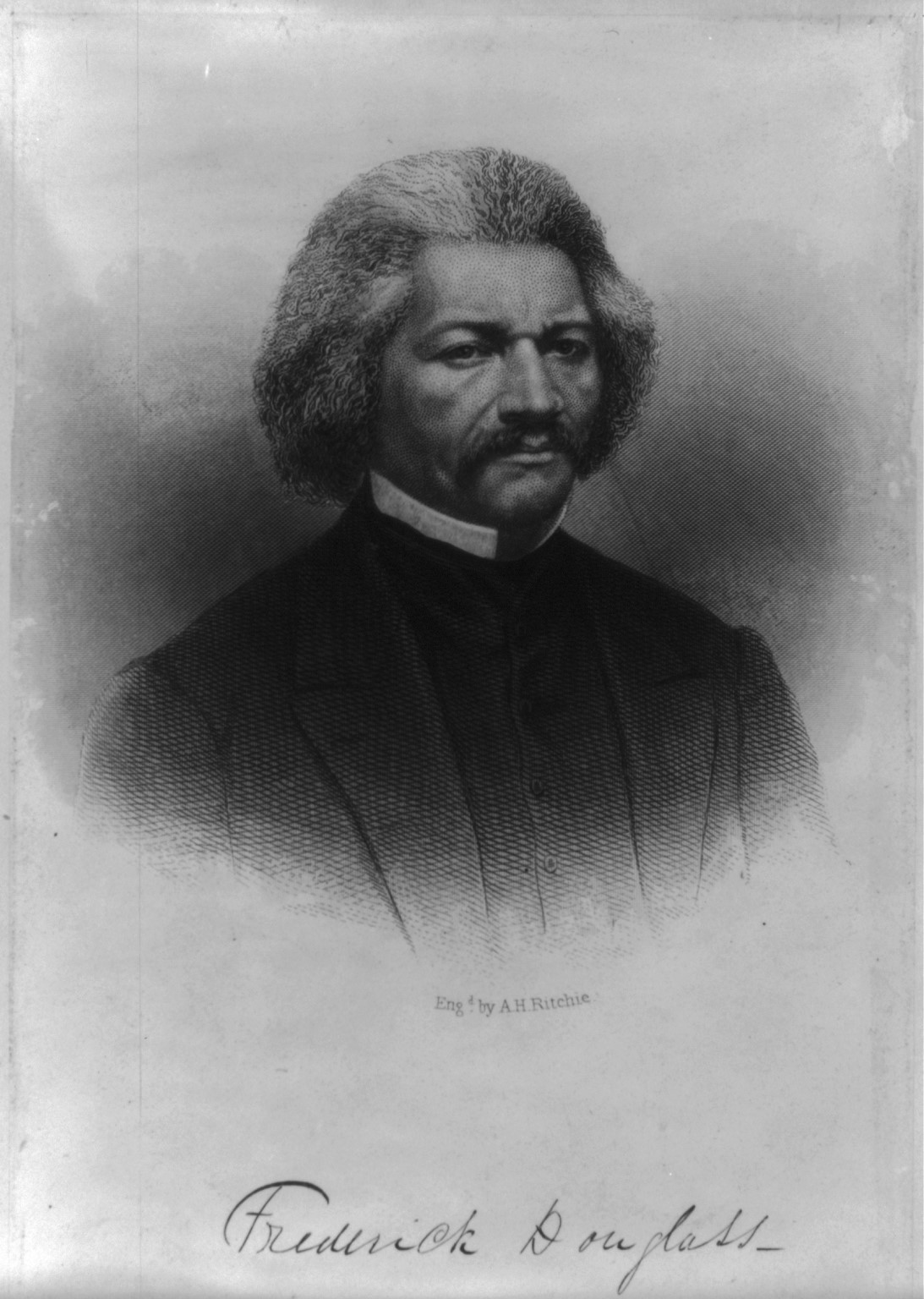

Soon after Gen. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, the war ended. Reconstruction was America’s attempt to rebuild—which opened up an opportunity for women’s suffrage. The Republican Party’s focus on civil and political rights for Southern black men made women’s suffrage seem politically possible. If Americans could use the national government to abolish slavery, why not use it to expand the franchise?

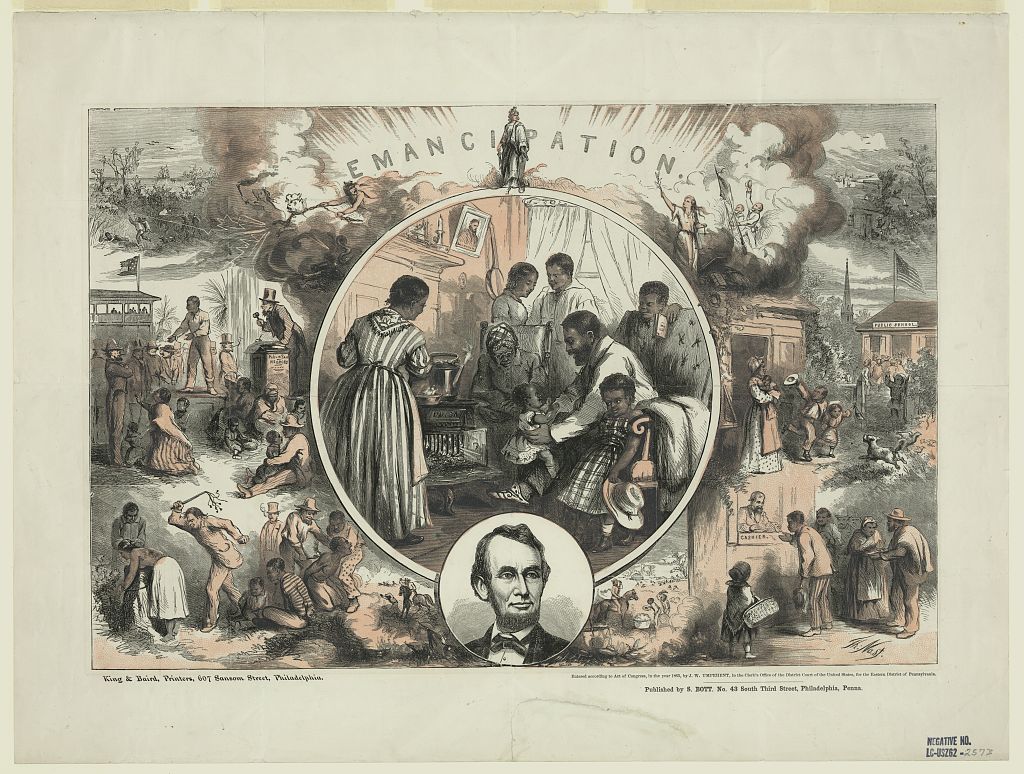

December 6, 1865

The 13th Amendment permanently outlawed slavery in the United States. Following decades of activism, resistance, and rebellion, abolitionists—including many women—finally saw their efforts inscribed into the Constitution. With slavery’s abolition, individual rights claims moved to the center of the American political agenda. Might universal suffrage be next?

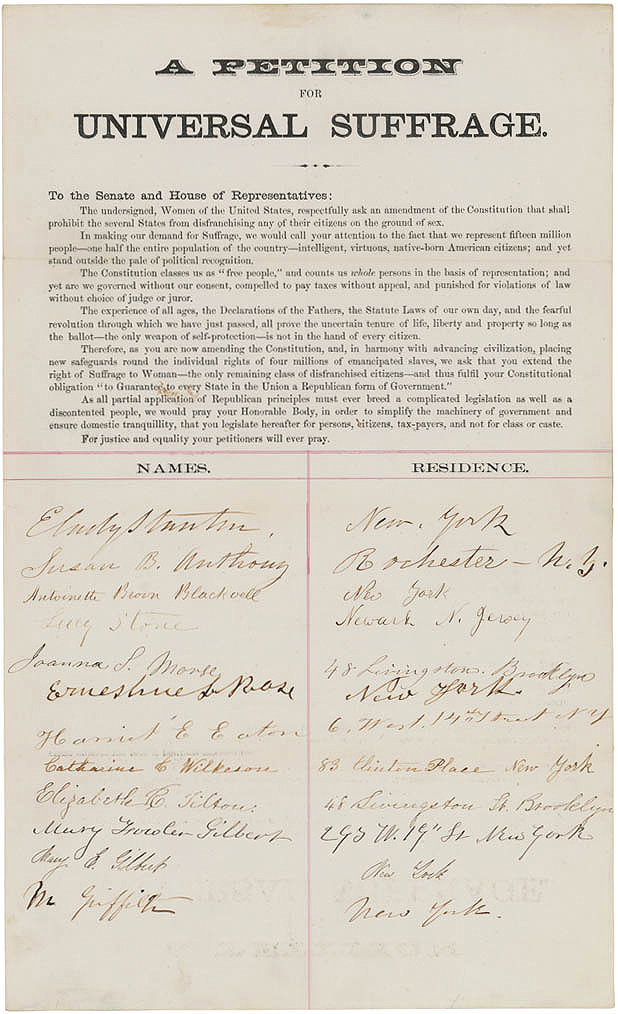

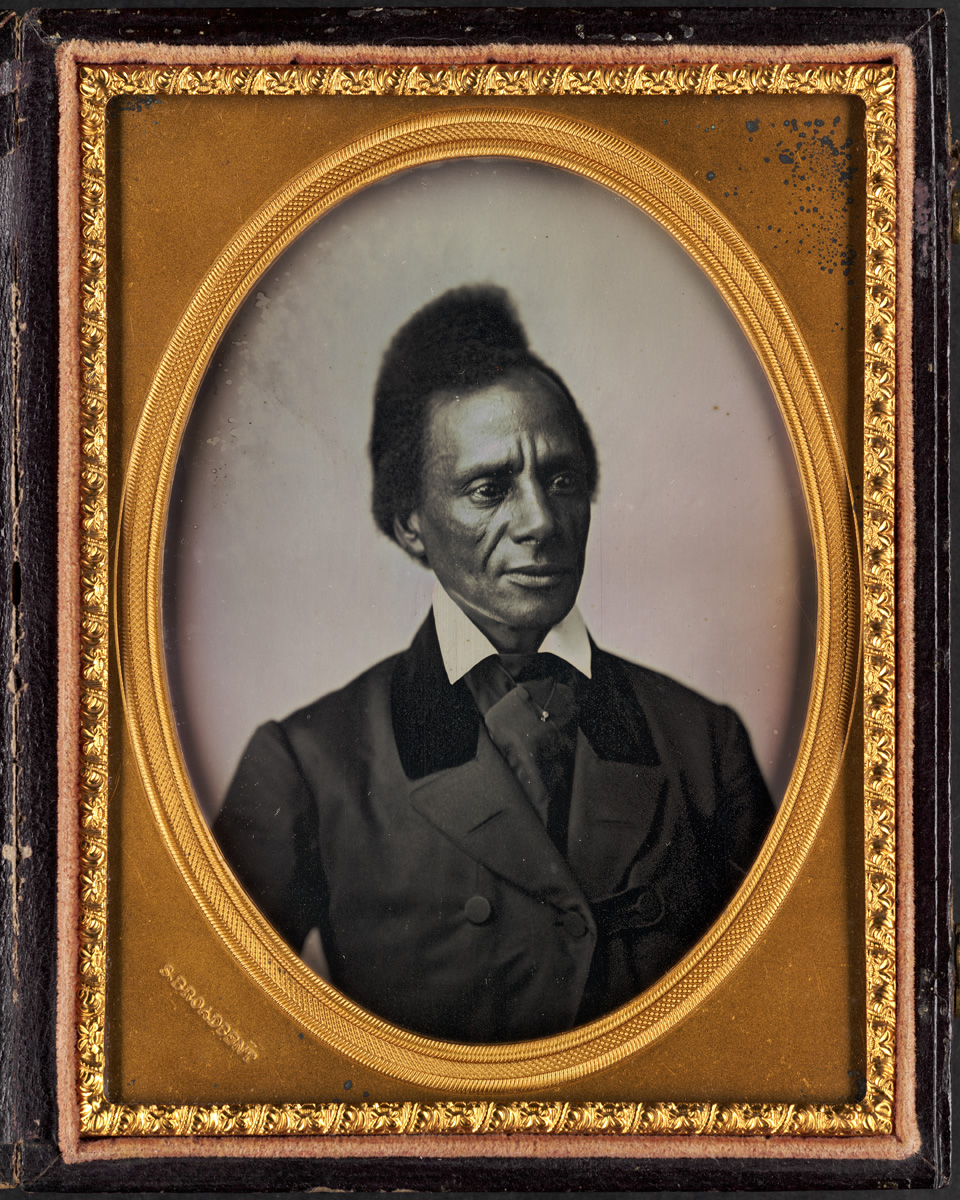

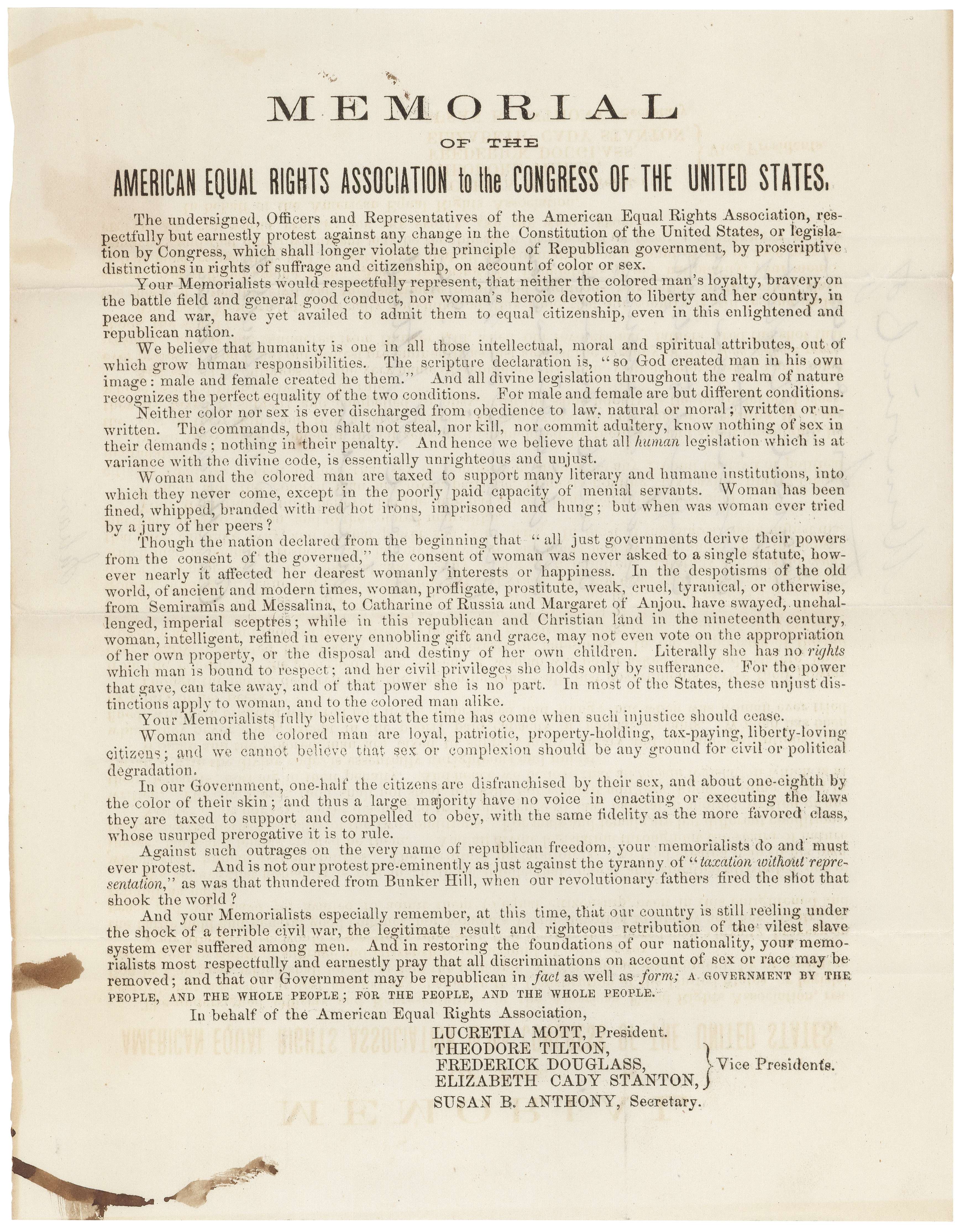

At the outset of Reconstruction, abolitionists and suffragists built a biracial coalition and united around a vision of universal suffrage—one that promoted the voting rights of both women and African-American men. They mobilized around this vision and flooded Congress with petitions. In 1866, these reformers founded the American Equal Rights Association (AERA).

The 14th Amendment promoted equal citizenship, but it introduced the word “male” into the Constitution for the first time—threatening to reduce congressional seats for states that did not allow all male citizens over 21 to vote. Some suffragists fought against this discriminatory language, but the amendment was ultimately ratified. As Congress prioritized African-American rights, tensions grew.

December 7, 1868

In 1867, supporters of universal suffrage campaigned for two referenda in Kansas, one seeking African-American male suffrage and the other women’s suffrage. Both referenda failed. Kansas Senator Samuel Pomeroy then brought this proposal to the Senate. The Senate let Senator Pomeroy's proposal lie on the table and never voted on it.

December 7, 1868

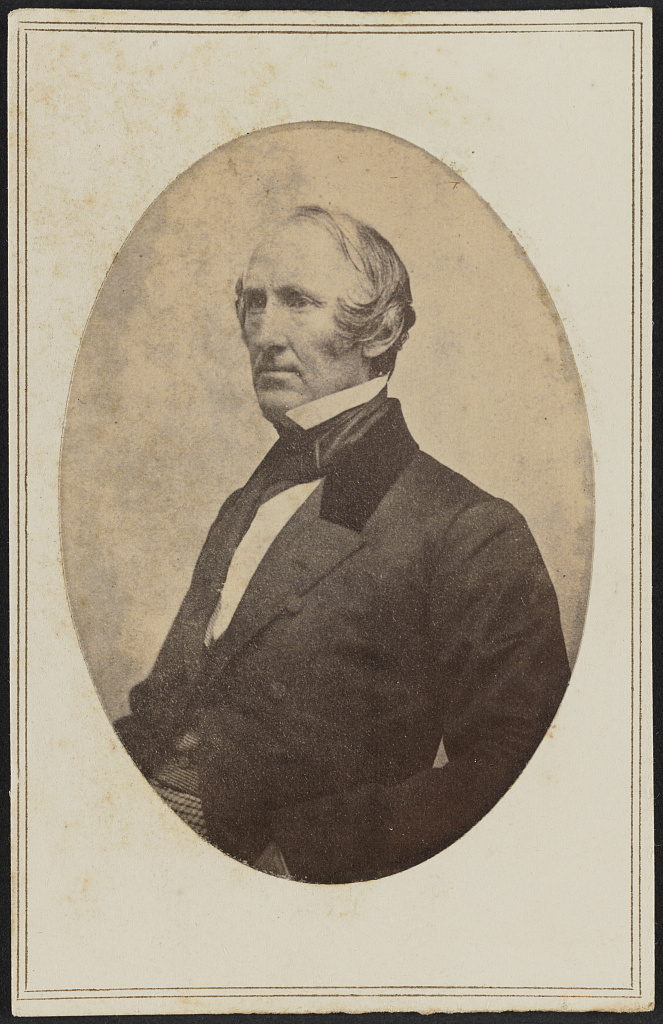

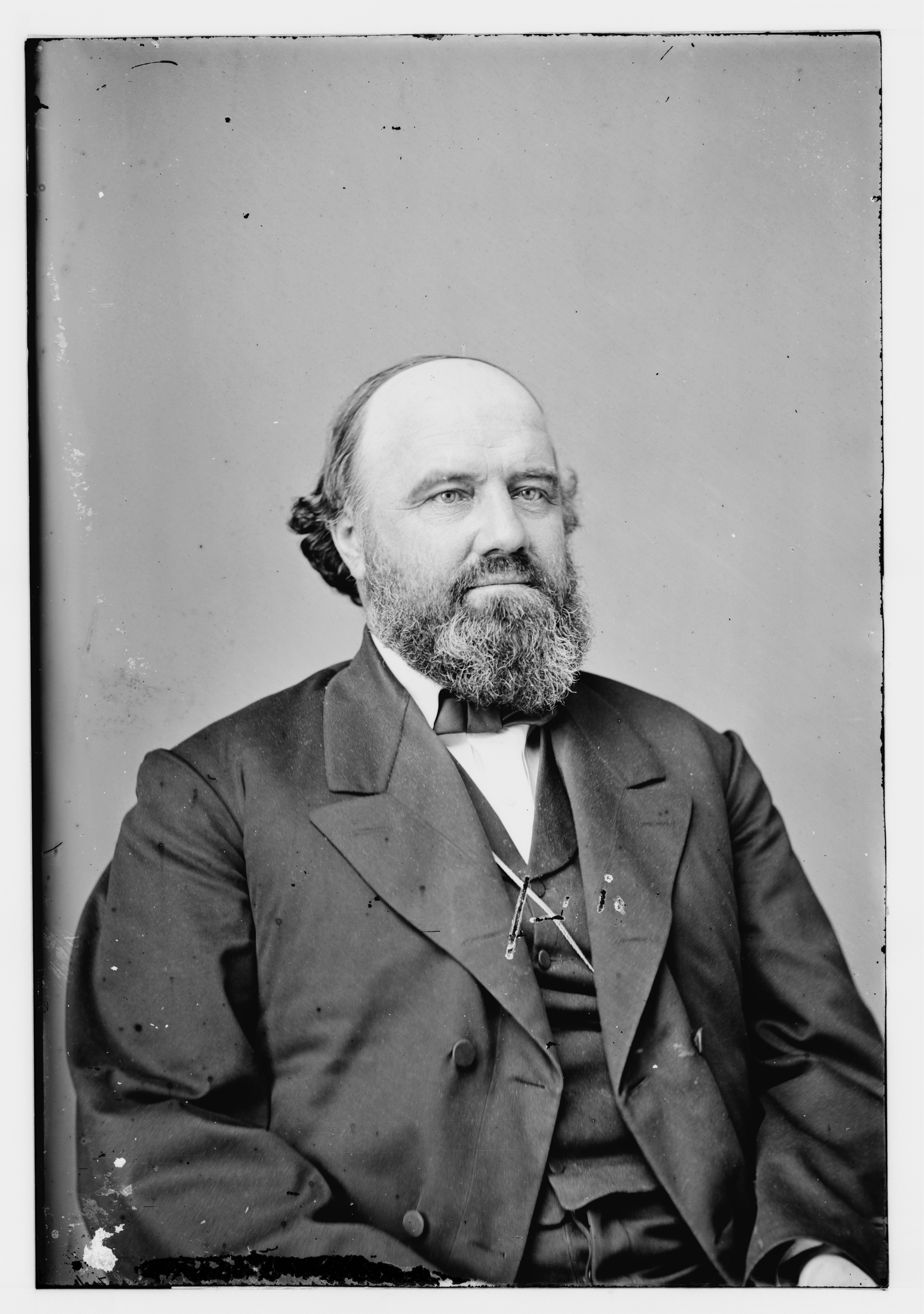

Samuel Pomeroy

U.S. Senator, Republican, Kansas

The basis of suffrage in the United States shall be that of citizenship, and all native or naturalized citizens shall enjoy the same rights and privileges of the elective franchise; Pomeroy's proposal embraced a broad vision of universal suffrage—advancing equal voting rights for both women and African-American men. Rather than basing voting rights on race or gender, Pomeroy rooted them in citizenship. but each State shall determine by law the age of the citizen and the time of residence required for the exercise of the right of suffrage, which shall apply equally to all citizens, and also shall make all laws concerning the time, places, and manner of holding elections. Pomeroy preserved an important role for the states to regulate voting rights—permitting them to determine the age and residency requirements of their voters and allowing them to regulate the “time, place, and manner of holding elections.”

Select highlighted text to view analysis.December 7, 1868

Samuel Pomeroy

U.S. Senator, Republican, Kansas

The basis of suffrage in the United States shall be that of citizenship, and all native or naturalized citizens shall enjoy the same rights and privileges of the elective franchise; Pomeroy's proposal embraced a broad vision of universal suffrage—advancing equal voting rights for both women and African-American men. Rather than basing voting rights on race or gender, Pomeroy rooted them in citizenship. but each State shall determine by law the age of the citizen and the time of residence required for the exercise of the right of suffrage, which shall apply equally to all citizens, and also shall make all laws concerning the time, places, and manner of holding elections. Pomeroy preserved an important role for the states to regulate voting rights—permitting them to determine the age and residency requirements of their voters and allowing them to regulate the “time, place, and manner of holding elections.”

Select a Document

December 8, 1868

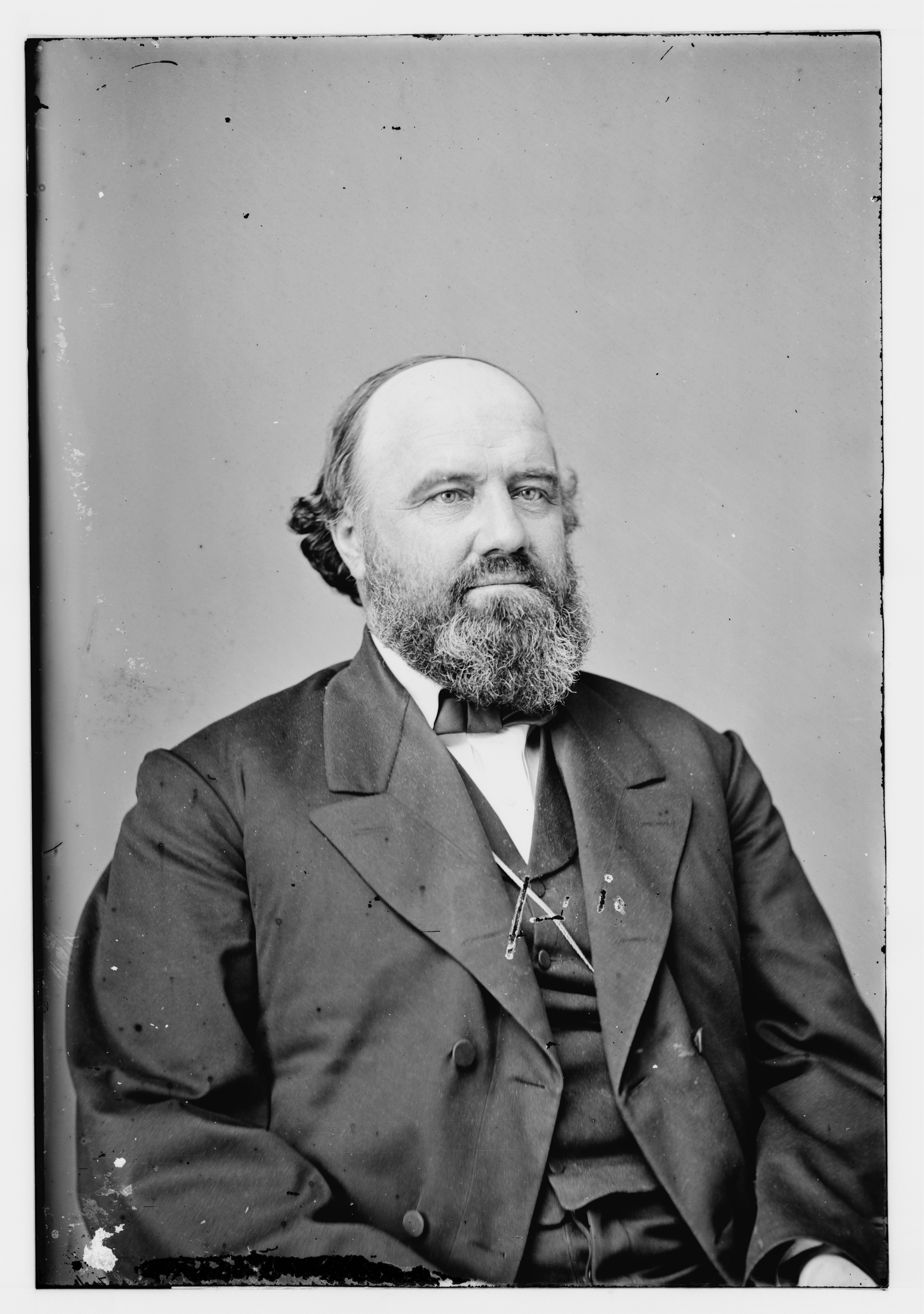

Three months before Congress passed the 15th Amendment, Rep. George Julian proposed a broad amendment—one that tied suffrage to citizenship and promised equal voting rights to all American citizens regardless of “race, color, or sex.” Julian's proposal attracted minimal support. The House referred it to the Committee on the Judiciary, but it was never put to a vote.

December 8, 1868

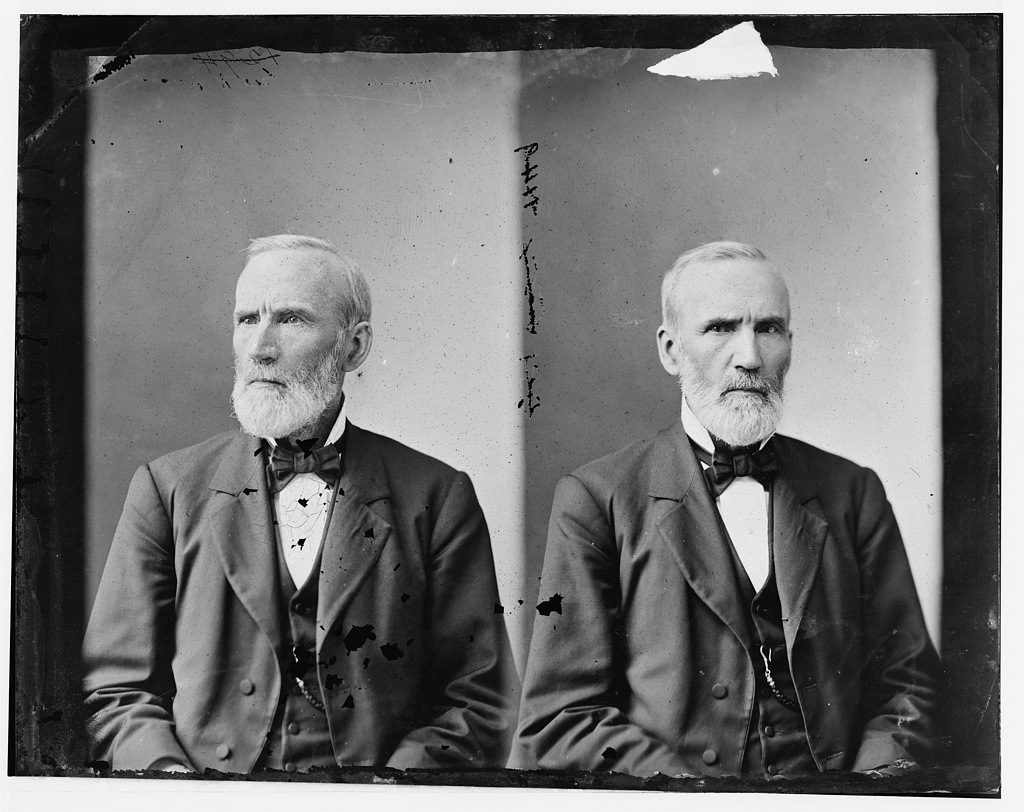

George Julian

U.S. Representative, Republican, Indiana

The right of suffrage in the United States shall be based upon citizenship, Julian's proposal severed the link between voting and specific traits like race or gender. Instead, it made voting a right of citizenship. and shall be regulated by Congress; While the original Constitution left the issue of voting primarily to the states, Julian's proposal empowered Congress to regulate voting rights. and all citizens of the United States, whether native or naturalized, shall enjoy this right equally, without any distinction or discrimination whatever founded on race, color, or sex. While the 15th Amendment would ultimately focus on racial discrimination in voting, Julian's proposal advanced a broad vision of suffrage—protecting the “right of suffrage” of all U.S. citizens regardless of “race, color, or sex.”

Select highlighted text to view analysis.December 8, 1868

George Julian

U.S. Representative, Republican, Indiana

The right of suffrage in the United States shall be based upon citizenship, Julian's proposal severed the link between voting and specific traits like race or gender. Instead, it made voting a right of citizenship. and shall be regulated by Congress; While the original Constitution left the issue of voting primarily to the states, Julian's proposal empowered Congress to regulate voting rights. and all citizens of the United States, whether native or naturalized, shall enjoy this right equally, without any distinction or discrimination whatever founded on race, color, or sex. While the 15th Amendment would ultimately focus on racial discrimination in voting, Julian's proposal advanced a broad vision of suffrage—protecting the “right of suffrage” of all U.S. citizens regardless of “race, color, or sex.”

Select a Document

January 29, 1869

A little under a month before Congress approved the 15th Amendment, Sen. Samuel Pomeroy proposed another suffrage amendment—the broadest voting rights proposal offered by anyone in Congress during the debates over the 15th Amendment. Pomeroy presented the amendment language to the Senate. The Senate did not adopt it.

January 29, 1869

Samuel Pomeroy

U.S. Senator, Republican, Kansas

The right of citizens of the United States to vote and hold office shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State for any reasons not equally applicable to all citizens of the United States. Pomeroy's proposal spoke broadly about voting rights and extended protections for officeholding. Although Congress debated the right to hold office, it didn't make it into the 15th Amendment—or the 19th. This proposal didn’t limit protections to “race” or “sex.” It protected the voting rights of “all citizens.” This language provided the national government with clear authority to attack white Southern efforts to suppress voting like poll taxes.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.January 29, 1869

Samuel Pomeroy

U.S. Senator, Republican, Kansas

The right of citizens of the United States to vote and hold office shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State for any reasons not equally applicable to all citizens of the United States. Pomeroy's proposal spoke broadly about voting rights and extended protections for officeholding. Although Congress debated the right to hold office, it didn't make it into the 15th Amendment—or the 19th. This proposal didn’t limit protections to “race” or “sex.” It protected the voting rights of “all citizens.” This language provided the national government with clear authority to attack white Southern efforts to suppress voting like poll taxes.

Select a Document

Once Congress passed the 15th Amendment, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony pushed their allies to propose a women’s suffrage amendment. Rep. George Julian offered this proposal less than three weeks after the 15th Amendment's passage. Julian's proposal was referred to the Committee on the Judiciary.

March 15, 1869

George Julian

U.S. Representative, Republican, Indiana

The right of suffrage in the United States shall be based upon citizenship, This opening language is identical to Julian's previous proposal from 1868. It severed the link between voting and specific traits like race or gender. Instead, it made voting a right of citizenship. and shall be regulated by Congress; This language is identical to Julian's previous proposal from 1868. While the original Constitution left the issue of voting primarily to the states, Julian's proposal empowered Congress to regulate voting rights. and all citizens of the United States, whether native or naturalized, shall enjoy this right equally, without any distinction or discrimination whatever founded on sex. Julian’s new proposal protected the “right to suffrage” of all U.S. citizens regardless of “sex.” He removed “race” and “color” from his previous draft. But it still left open the possibility of regulating the vote based on traits such as literacy.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.March 15, 1869

George Julian

U.S. Representative, Republican, Indiana

The right of suffrage in the United States shall be based upon citizenship, This opening language is identical to Julian's previous proposal from 1868. It severed the link between voting and specific traits like race or gender. Instead, it made voting a right of citizenship. and shall be regulated by Congress; This language is identical to Julian's previous proposal from 1868. While the original Constitution left the issue of voting primarily to the states, Julian's proposal empowered Congress to regulate voting rights. and all citizens of the United States, whether native or naturalized, shall enjoy this right equally, without any distinction or discrimination whatever founded on sex. Julian’s new proposal protected the “right to suffrage” of all U.S. citizens regardless of “sex.” He removed “race” and “color” from his previous draft. But it still left open the possibility of regulating the vote based on traits such as literacy.

Select a Document

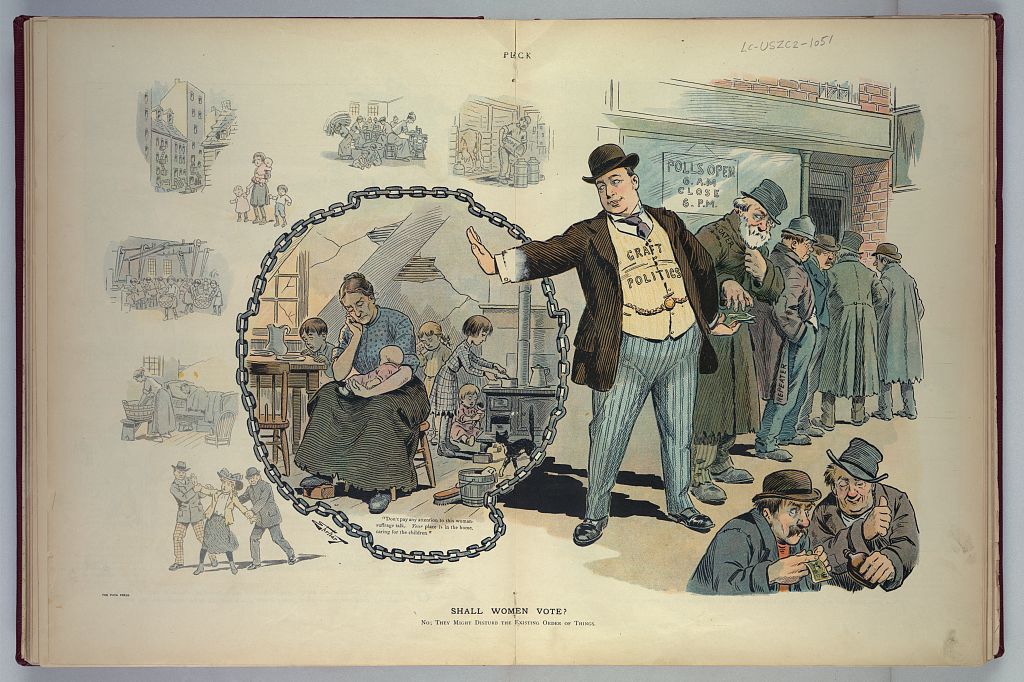

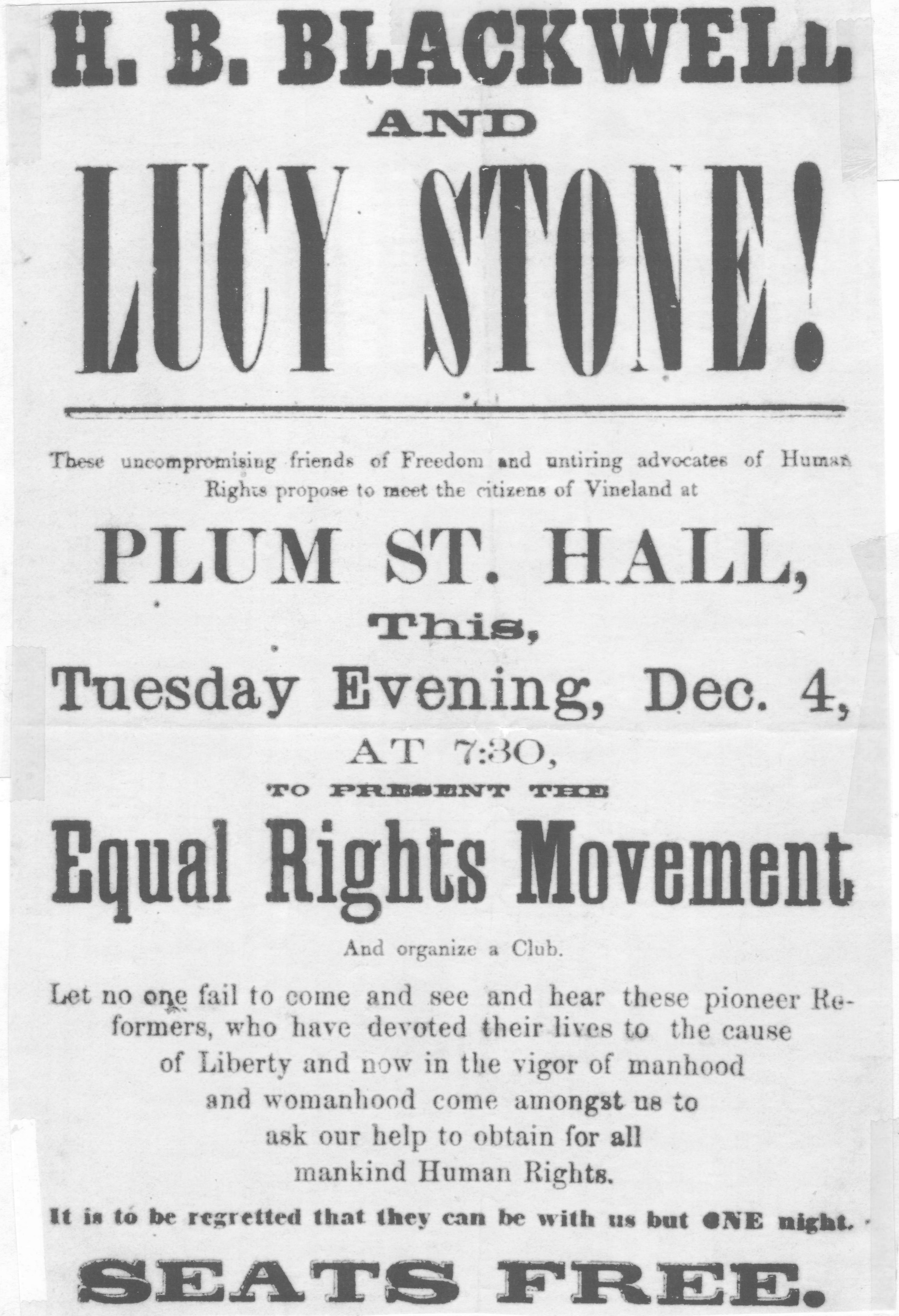

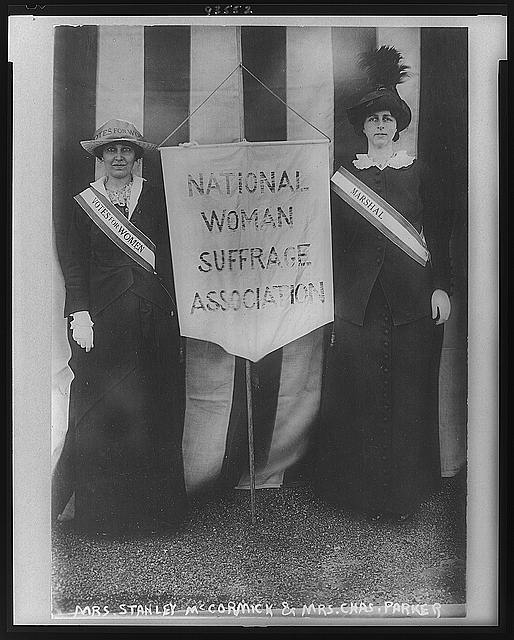

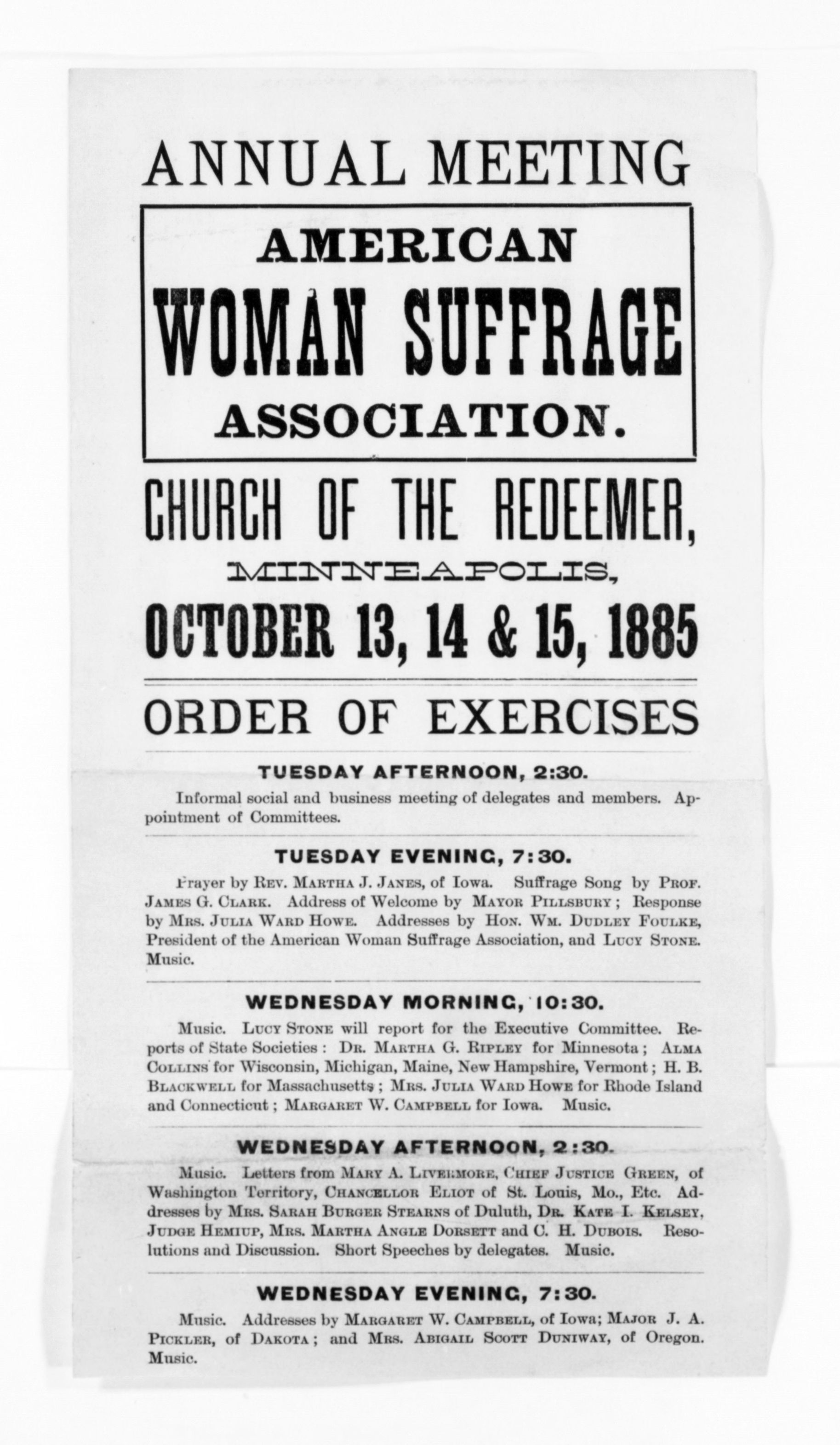

The movement disagreed over strategy and the proposed 15th Amendment—causing the American Equal Rights Association to split. The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) formed in May, and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) organized in November. While the AWSA supported the 15th Amendment, the NWSA opposed it—turning away from its longtime abolitionist allies.

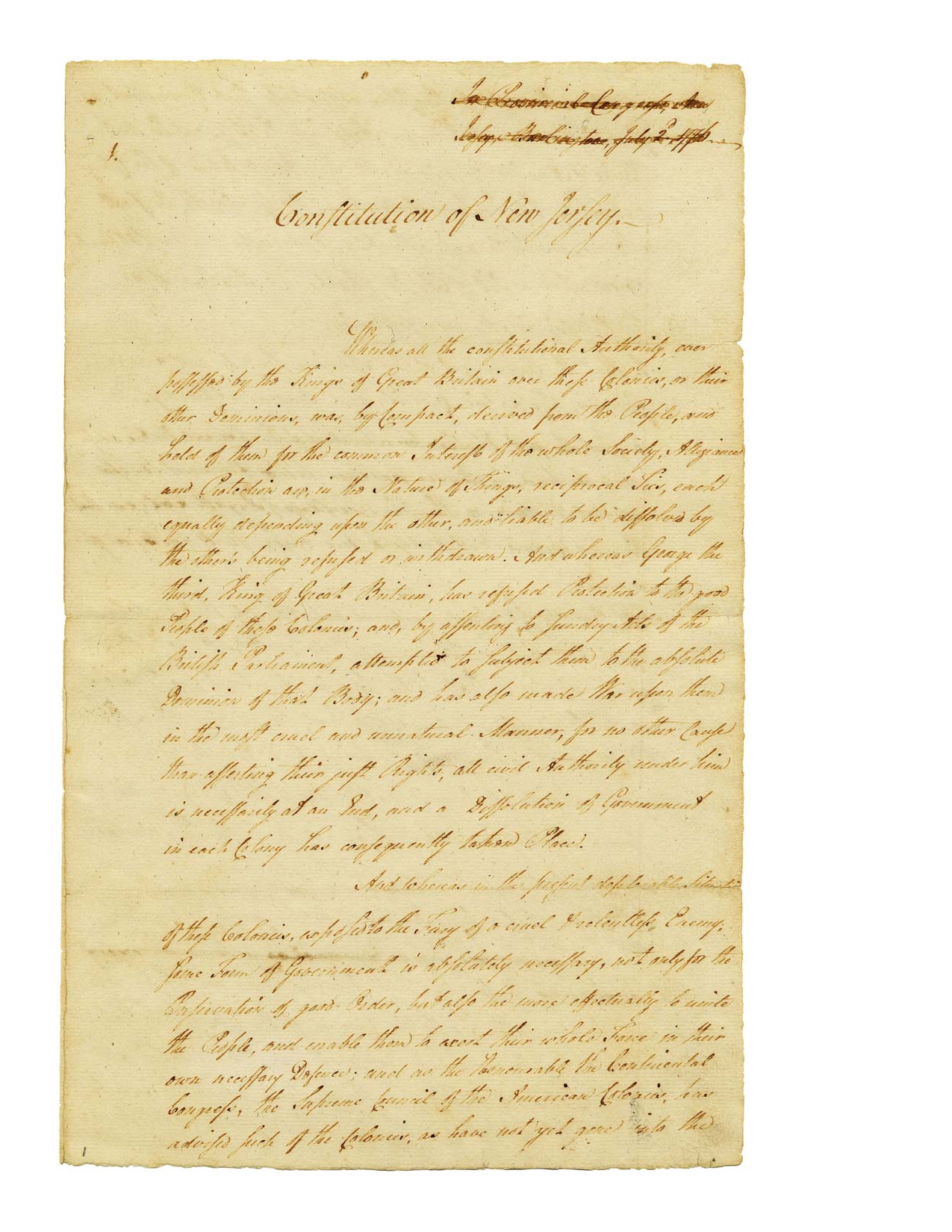

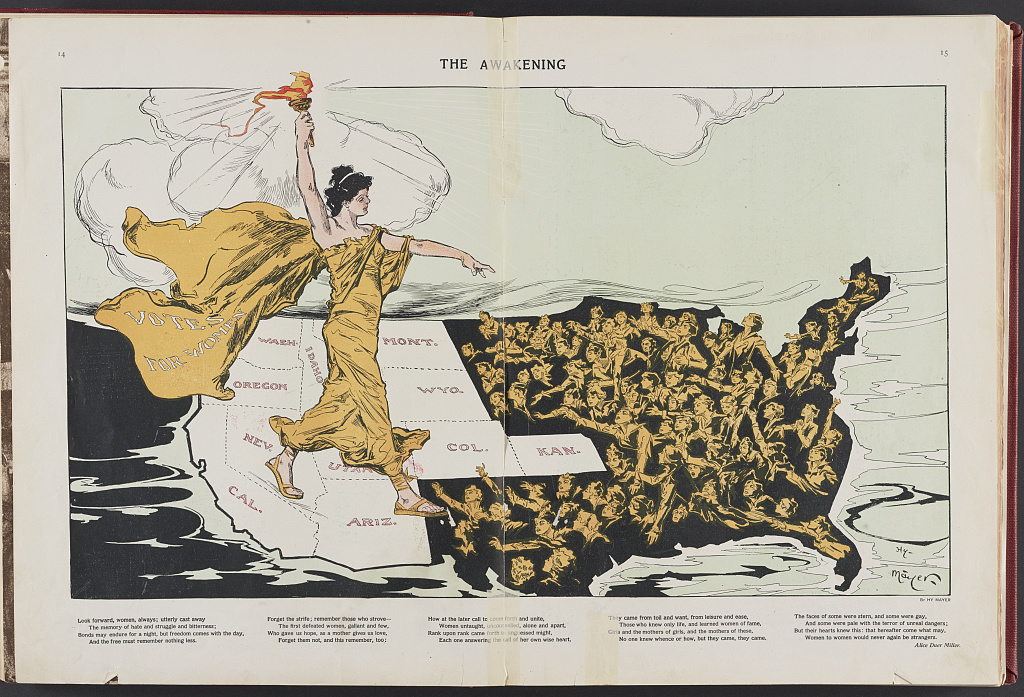

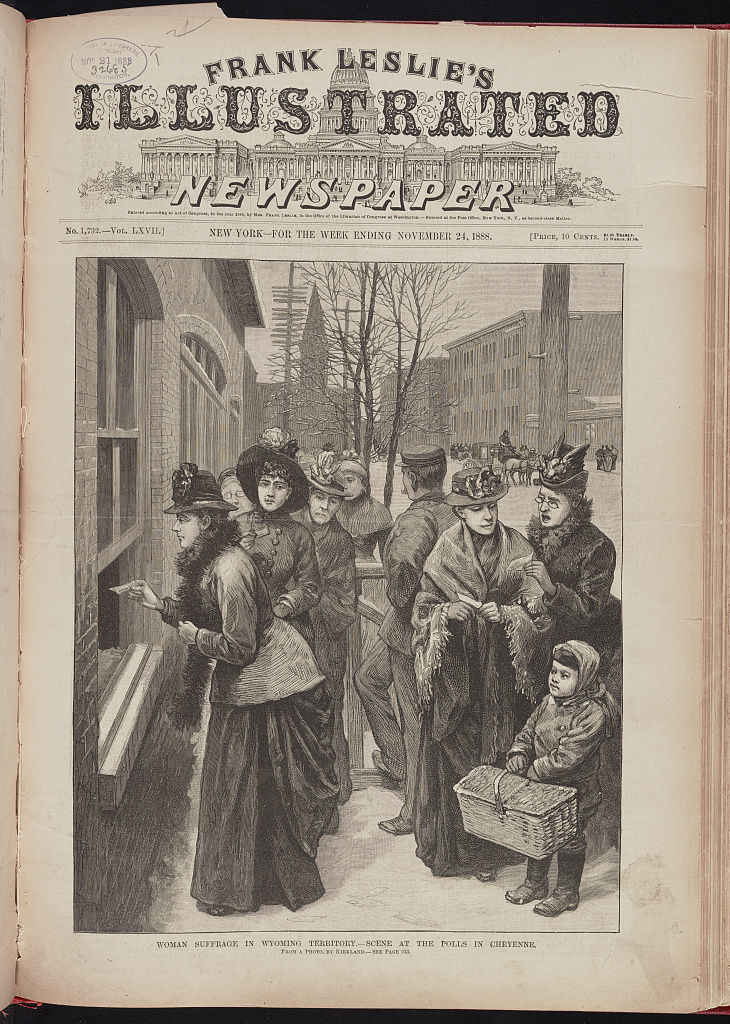

December 10, 1869

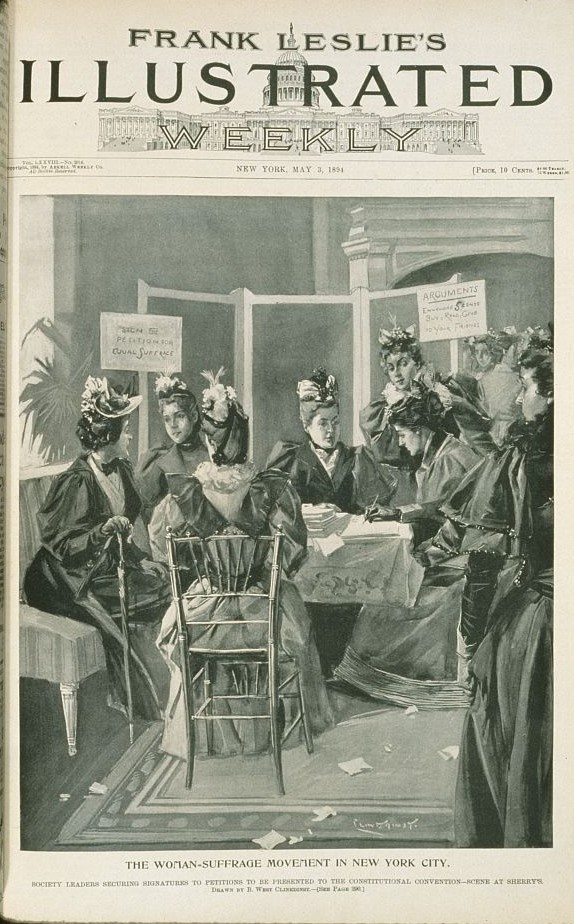

In 1869, the Wyoming Territory became the first to grant women full suffrage. While some suffragists focused on a national amendment, others insisted that voting had to be won at the state level. State constitutions spelled out who could vote—and who could not. Since states required voters be “male,” suffragists sought to strike that word from state constitutions throughout the nation.

February 3, 1870

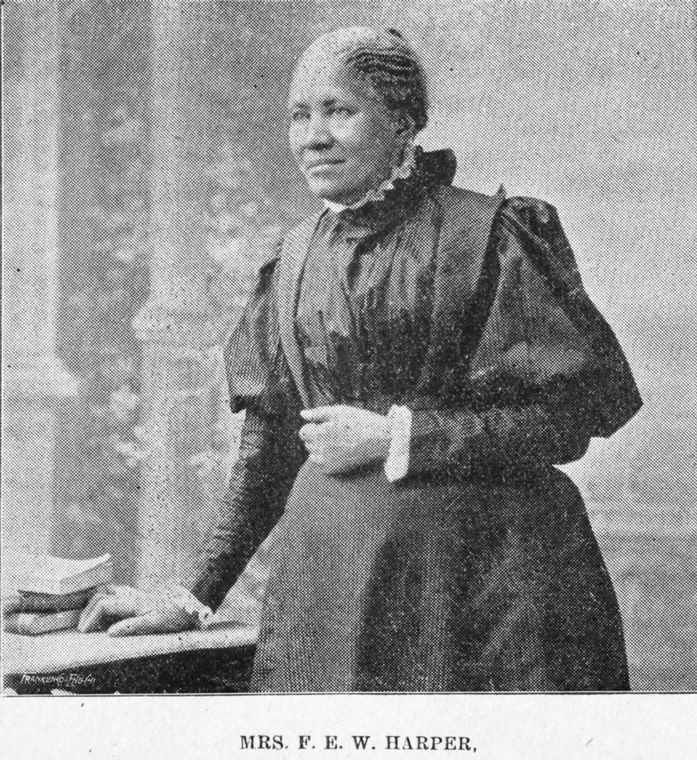

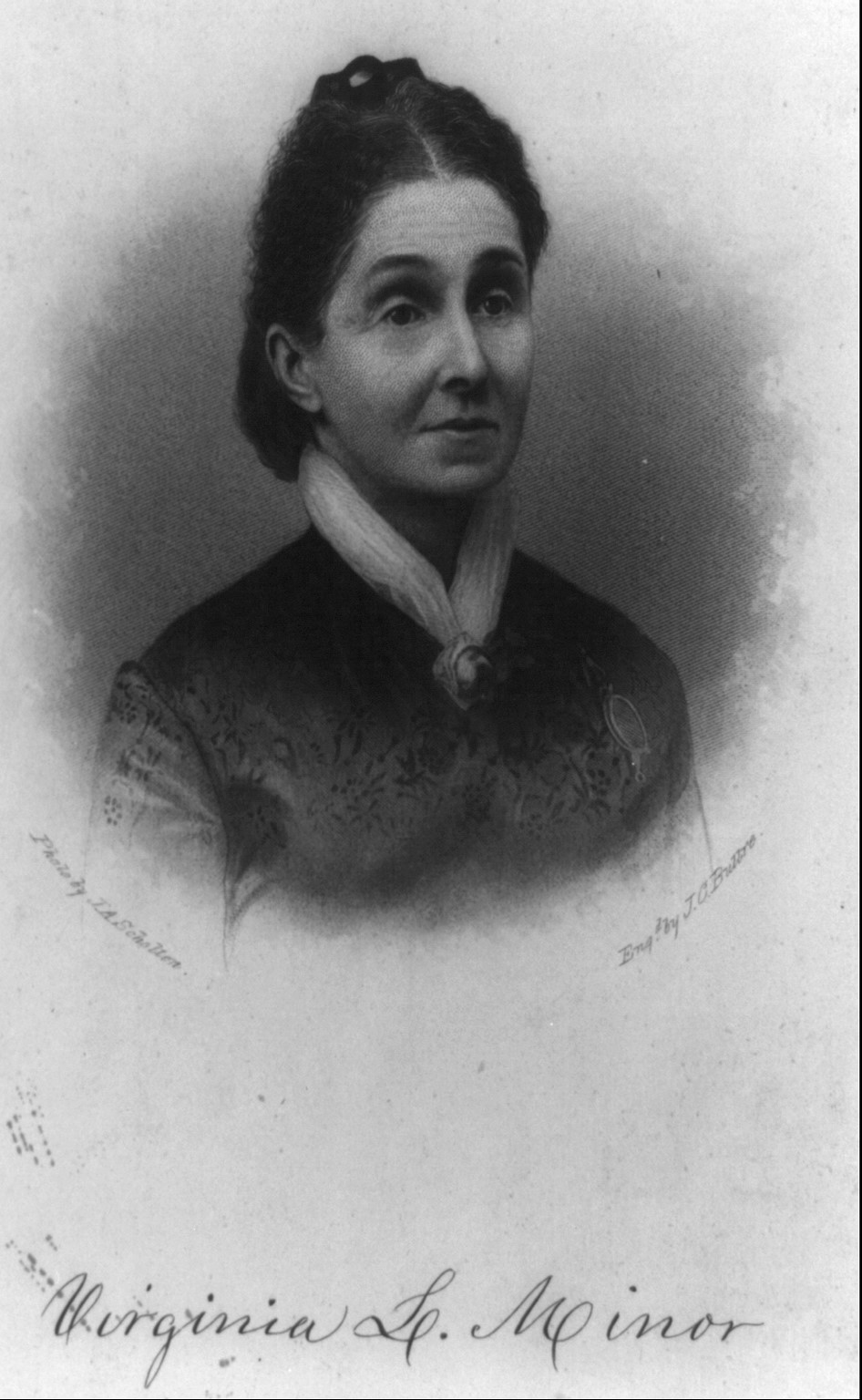

The 15th Amendment, ratified by the states in 1870, protected the voting rights of African-American men. Some white suffragists were appalled by their exclusion; these women adopted racist arguments, further fracturing the universal suffrage movement. The suffragists reassessed their tactics.

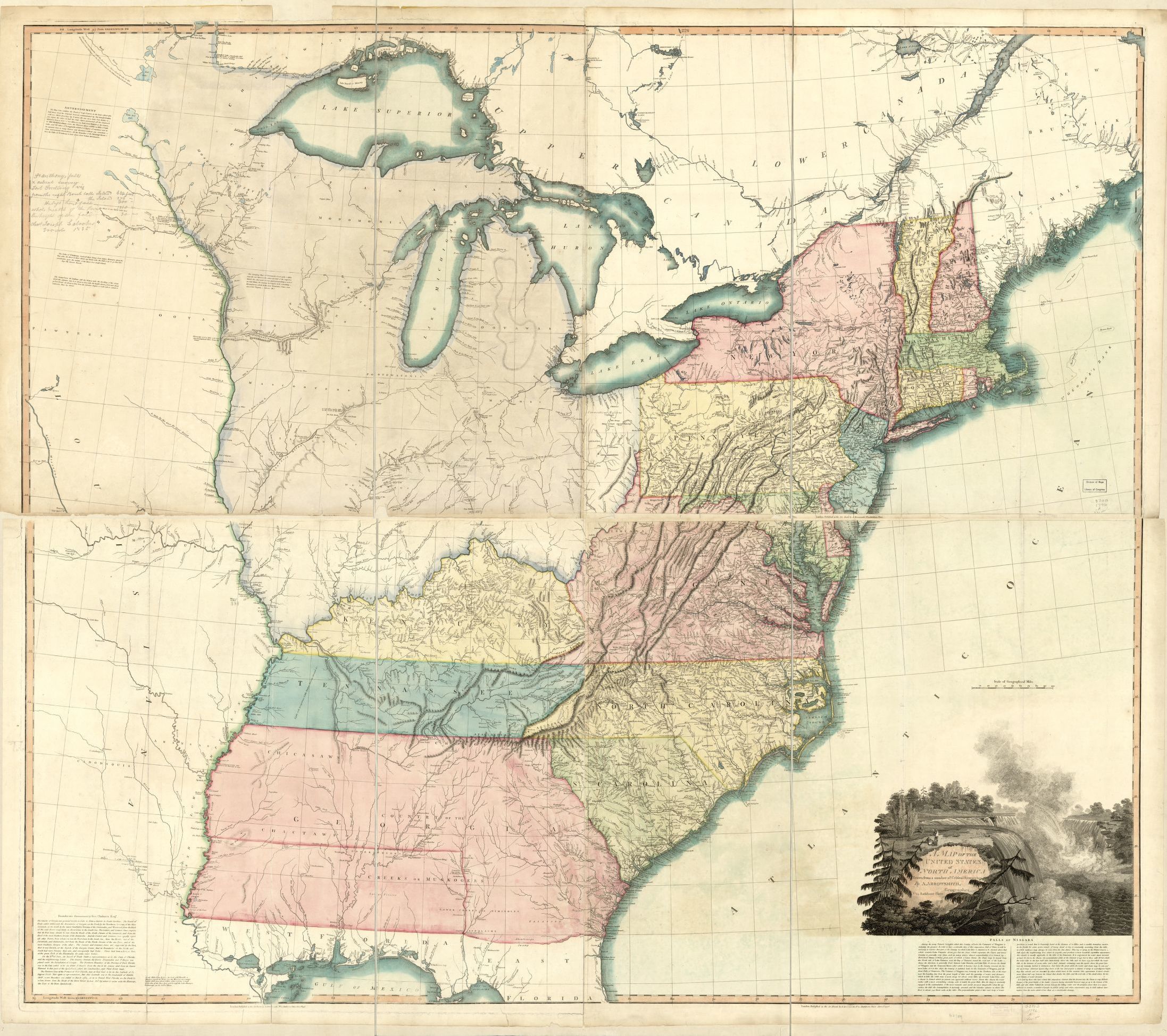

November 5, 1872

Many suffragists, including Susan B. Anthony in 1872, tried to vote under the 14th Amendment. With this “New Departure” plan, women argued that the amendment already protected this right. From 1868 to 1875, hundreds of women tried to register and vote. A few were successful based on where they lived, but many more were not. Some even took their case to court.

The nation celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence in 1876 in Philadelphia. Denied a spot in the program, suffragists crashed the ceremony. The National Woman Suffrage Association crafted their own Declaration of Rights—adopting the language “no taxation without representation” while calling for suffrage and equality.

January 10, 1878

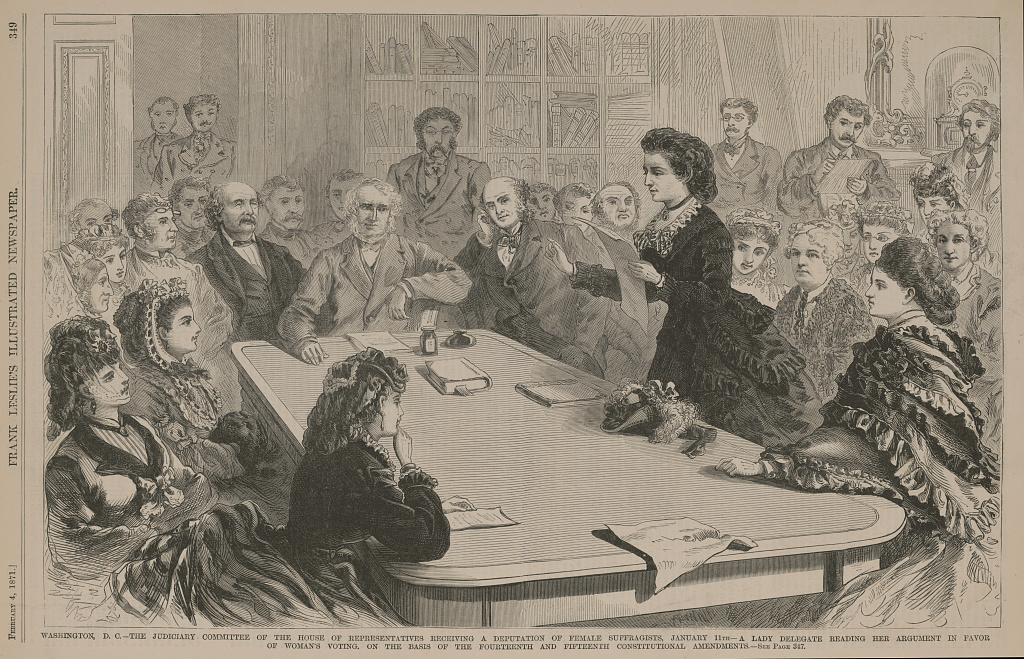

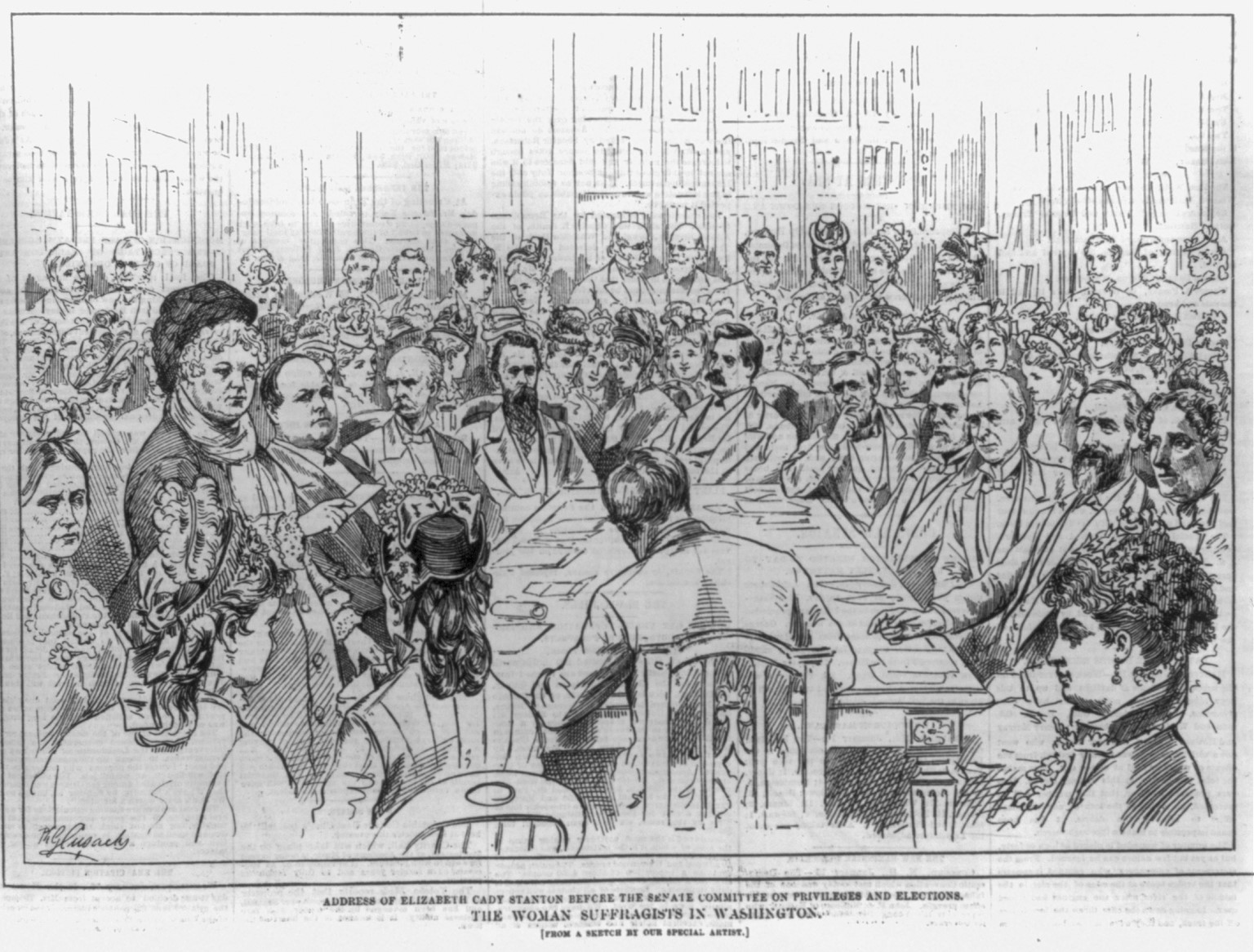

At the urging of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, Sen. Aaron Sargent introduced this proposal—known as the “Susan B. Anthony Amendment.” Introduced in each Congress over the next four decades, it eventually became the 19th Amendment. Sargent's proposal was referred to the Committee on Privileges and Elections. The day after it was proposed, suffragists including Stanton testified before the committee. In the end, the committee voted to have the proposal “indefinitely postponed.”

January 10, 1878

Aaron Sargent

U.S. Senator, Republican, California

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. This opening language parallels the 15th Amendment—beginning with a powerful reference to a U.S. citizen's “right . . . to vote.” Sargent abandoned the language of universal suffrage. He borrowed from the 15th Amendment—but changed “race, color, or previous condition of servitude” to “sex.” This left open the possibility of regulating the vote based on traits such as literacy. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. The original Constitution left the issue of voting primarily to the states. Like the 15th Amendment, Sargent's proposal provided Congress with a new role in enforcing voting rights—this time, to prevent gender discrimination at the ballot box.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.January 10, 1878

Aaron Sargent

U.S. Senator, Republican, California

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. This opening language parallels the 15th Amendment—beginning with a powerful reference to a U.S. citizen's “right . . . to vote.” Sargent abandoned the language of universal suffrage. He borrowed from the 15th Amendment—but changed “race, color, or previous condition of servitude” to “sex.” This left open the possibility of regulating the vote based on traits such as literacy. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. The original Constitution left the issue of voting primarily to the states. Like the 15th Amendment, Sargent's proposal provided Congress with a new role in enforcing voting rights—this time, to prevent gender discrimination at the ballot box.

Select a Document

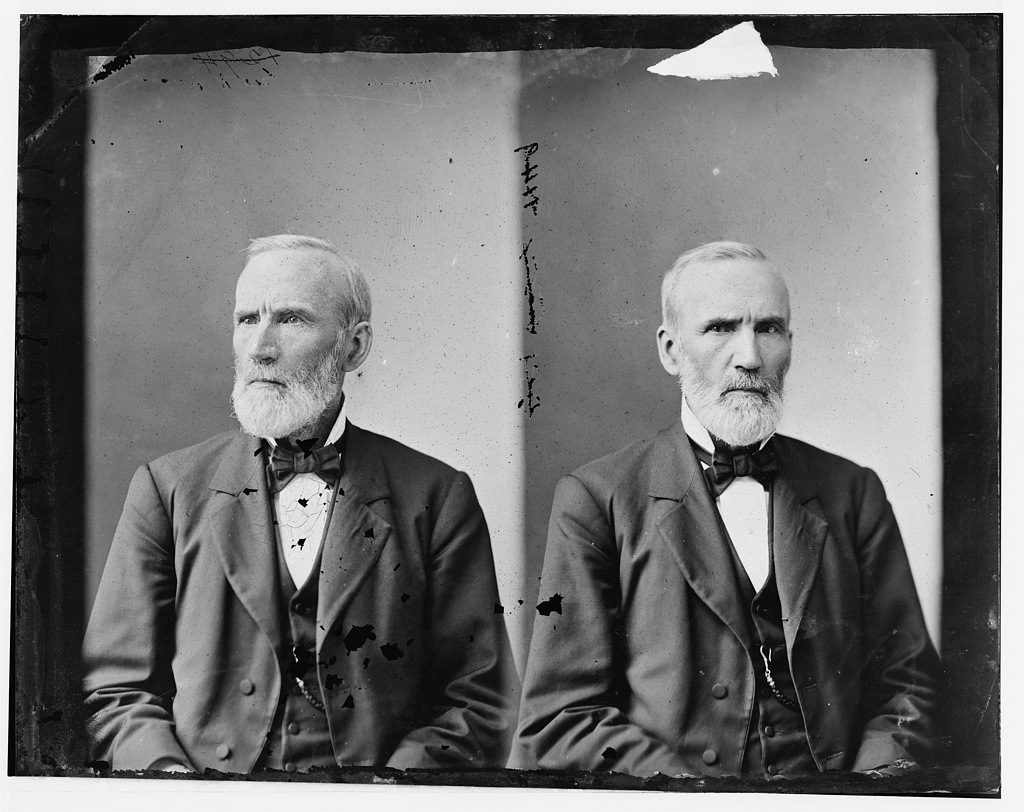

Rep. John White introduced this draft in the House, mirroring Sargent's 1878 proposal. It was referred to the Select Committee on Woman Suffrage.

July 10, 1882

John D. White

U.S. Representative, Republican, Kentucky

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. This opening language parallels the 15th Amendment—beginning with a powerful reference to a U.S. citizen's “right . . . to vote.” This draft focused on sex discrimination in voting. Borrowing from the 15th Amendment, it changed “race, color, or previous condition of servitude” to “sex.” This text left open the possibility of regulating the vote based on traits such as literacy. The Congress shall have power by appropriate legislation to enforce the provisions of this article. The original Constitution left the issue of voting primarily to the states. Like the 15th Amendment, this proposal provided Congress with a new role in enforcing voting rights—this time, to prevent gender discrimination at the ballot box.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.July 10, 1882

John D. White

U.S. Representative, Republican, Kentucky

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. This opening language parallels the 15th Amendment—beginning with a powerful reference to a U.S. citizen's “right . . . to vote.” This draft focused on sex discrimination in voting. Borrowing from the 15th Amendment, it changed “race, color, or previous condition of servitude” to “sex.” This text left open the possibility of regulating the vote based on traits such as literacy. The Congress shall have power by appropriate legislation to enforce the provisions of this article. The original Constitution left the issue of voting primarily to the states. Like the 15th Amendment, this proposal provided Congress with a new role in enforcing voting rights—this time, to prevent gender discrimination at the ballot box.

Select a Document

In 1884, the Select Committee on Woman Suffrage recommended that the Senate adopt this proposal. It drew on language from a women's suffrage petition sent to the Senate Judiciary Committee four years earlier. The Senate Select Committee on Woman Suffrage proposed this amendment to the Senate for adoption in 1884. The Senate voted down a women's suffrage amendment in 1887 (16-34).

March 28, 1884

Senate Select Committee on Woman Suffrage

Committee created on January 9, 1882

The right of suffrage in the United States shall be based on citizenship, and the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States, or by any State, on account of sex, or for any reason not equally applicable to all citizens of the United States. This language was identical to Representative George Julian's proposals in the late 1860s. It severed the link between voting and specific traits like race or gender. Instead, it made voting a right of citizenship. This draft used the 15th Amendment’s “shall not” language and changed “race, color, or previous condition of servitude” to “sex.” It also gave the national government clear authority to attack voter suppression efforts like poll taxes and literacy tests. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. The original Constitution left voting primarily to the states. Like the 15th Amendment and previous women's suffrage proposals, this draft provided Congress with a new role in enforcing voting rights.

Select highlighted text to view analysis.March 28, 1884

Senate Select Committee on Woman Suffrage

Committee created on January 9, 1882

The right of suffrage in the United States shall be based on citizenship, and the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States, or by any State, on account of sex, or for any reason not equally applicable to all citizens of the United States. This language was identical to Representative George Julian's proposals in the late 1860s. It severed the link between voting and specific traits like race or gender. Instead, it made voting a right of citizenship. This draft used the 15th Amendment’s “shall not” language and changed “race, color, or previous condition of servitude” to “sex.” It also gave the national government clear authority to attack voter suppression efforts like poll taxes and literacy tests. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. The original Constitution left voting primarily to the states. Like the 15th Amendment and previous women's suffrage proposals, this draft provided Congress with a new role in enforcing voting rights.